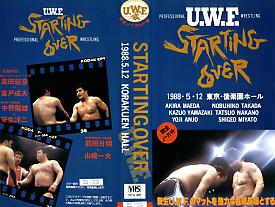

U.W.F. STARTING OVER U.W.F. Commercial Tape |

On April 8, 1988, former New Japan Pro-Wrestling stars Akira Maeda, Nobuhiko Takada, Kazuo Yamazaki held a press conference to announce the inpending debut of the Newborn U.W.F. Though the same stars attempt at creating a rival promotion based on “legitimate” pro-wrestling four years earlier had failed, causing them to come crawling back to New Japan in 1986, they were still determined to not only create an original form of professional wrestling called shooting style, but this time make it a sustainable business.

On April 8, 1988, former New Japan Pro-Wrestling stars Akira Maeda, Nobuhiko Takada, Kazuo Yamazaki held a press conference to announce the inpending debut of the Newborn U.W.F. Though the same stars attempt at creating a rival promotion based on “legitimate” pro-wrestling four years earlier had failed, causing them to come crawling back to New Japan in 1986, they were still determined to not only create an original form of professional wrestling called shooting style, but this time make it a sustainable business.

Their stars had risen considerably since the first attempt, with Takada & Yamazaki, who debuted in 1980 & 1982 respectively, now reaching their prime years and the NJPW vs. U.W.F. program that began when the defectors returned being a tremendously heated box office hit. That being said, the main thing that had changed is Maeda had become infamous for breaking rival Riki Choshu’s orbital bone in October 1987 with a cowardly shoot kick. Maeda was first suspended, then fired when he wouldn’t go along with New Japan’s reinstatement terms, so giving his own promotion a go seemed the best of his few options.

Power hungry Choshu was not a favorite of the other former UWF guys, if for no other reason than his return from AJPW took the spotlight off their main event program, soon shifting them to a secondary program amongst themselves where Yoshiaki Fujiwara & Yamazaki vied for Maeda & Takada’s tag titles. Takada & Yamazaki were most likely always going to be in about the same spot they already were, as while they’d begun to make some headway through tag title runs, they were still participating in the major junior heavyweight events such as the August 1987 title tournament and original Super Junior League in January through February 1988. Despite all their obvious talent, they pretty much only saw main events due to their association with Maeda, with even their tag title matches generally being behind Inoki and Choshu’s matches on the big shows. Thus, being Maeda’s main rivals seemed a logical gamble to staying in New Japan where even if they eventually fully graduated from the junior division, they’d more likely continue to be the rival of Shiro Koshinaka (he largely dominated the IWGP junior title since it’s inception, with his last reign ending about a year after the UWF wrestlers left) and perhaps the new sensation Hiroshi Hase, whose name recognition from the 1984 Olympics allowed him to immediately seize the junior title that had remained elusive to Yamazaki in his two attempts. In the end, all the former UWF members but Fujiwara (who was training Masakatsu Funaki & Minoru Suzuki) & Osamu Kido decided to follow Maeda to the new promotion.

The second U.W.F. was somewhat more MMA oriented than its predescessor, which relied more on old school grappling and locks that had become somewhat passe in puroresu through the introduction of (then) modern highspots. The emphasis was still on kick, suplex, and submission, but now you couldn’t just throw any technical wrestler in there, they had to have at least trained in faking martial arts to be successful. It wasn’t so much that the new U.W.F. was radically different from the old one, but rather they were able to market it as something revolutionary, and capitalize on the fans appreciation of the basis of their offense from NJPW, as well as their ever growing frustration with the constant, nonsensical screwjobs in the major promotions.

In an effort to garner immediate credibility, they invited several well known martial artists to their debut show, turning the spotlight on each of the big names from boxing and shootboxing community. At least one New Japan wrestler was present, their old cohort Fujiwara, a muay thai kickboxer in another lifetime who was better known for having the strongest head in puroresu (unless it was Allen Coage...) and would eventually become the U.W.F.’s 4th major star.

10 Minute Exhibition Match: Nobuhiko Takada vs. Shigeo Miyato 10:00. Sending the two flashiest fighters in the league out for an exhibition match was a somewhat interesting strategy to kick off a new promotion based on credibility. I suppose the logic is you have to take things down slowly, so going with the guys who were most similar to what the fans were used to would ease them in to the hardcore technical wrestling. Their match more believable than most of Takada's, with Miyato doing a good job making Takada look like a real force. Takada never looked big in New Japan, but he completely dwarfed Shigeo to the point you felt they should be calling his opponent Miyatocito. The match didn’t need to be particularly competitive since it was scheduled to continue for the full 10 minutes regardless of the number of finishes. Takada stopped Miyato’s Achilles’ tendon hold with one of his own just after the 6 minute mark and also tapped him with a cross armbar at 7 ½, but the contest was generally more of a squash than even a 2-0 sweep would suggest, too one-sided to have any real drama with the multiple falls largely just contributing to the feeling of irrelevance. Everything they did was well done though. **1/4

Yoji Anjo vs. Tatsuo Nakano 24:25. I didn’t care for this match too much the first time I saw it, but I guess I just didn’t have the patience for it at the time, as it now seems like one for the purists. It’s not a great bout for those who mainly care about the moves or kicks, but certainly really good technically, and definitely an exceptionally well crafted and laid out contest. Anjo always had A+ stamina, and seemed to enjoy doing long matches. This was one of most logical and best built he ever did, really putting a lot of thought into how they’d transition. The early portion was spent getting over the difficulty of attaining a position, leading to a pop when Nakano nearly countered Anjo’s reverse waistlock into a wakigatame. Anjo did seem to slip up using a jackknife hold then releasing when he realized the ref wasn’t going to count, but this spot did show the difference between the sort of wrestling they had been doing, and what they would be doing from now on. Anjo worked for an armbar, but Nakano eventually knocked him off with a kick, so Anjo stood over Nakano and began punting his shoulder. Anjo began incorporating his kicks now that he had a target, regularly but unsuccessfully trying to find an opening for the armbar. Anjo couldn’t get leverage for a wakigatame, so he tried a belly to belly suplex, only to have Nakano come to life with a headbutt and buckle him with body blows that left him prone for a snap suplex. They not only worked up to their heavy strikes and suplexes, but were careful to use them when the opposition was suitably tired and prone. The matwork wasn’t as believable as the better UWF-I & RINGS bouts we got after the style had evolved, and I could have lived without the ode to fakery represented by the dropkick, but all in all this was everything you could have asked for and then some. ****

Akira Maeda vs. Kazuo Yamazaki 24:56. An important match for U.W.F. because Yamazaki didn’t have enough heavyweight singles credibility to beat Maeda, but given two junior heavyweights were his only real opposition, Maeda had to make the audience believe they were a lot closer to his standing than their singles resumes would have suggested. It obviously helped that Yamazaki & Takada were among the most talented workers of their era, but the match worked so well because they approached it intelligently. They couldn’t just say, this junior heavyweight is as tough as a man who had been more or less on the level with Antonio Inoki, Tatsumi Fujinami, & Choshu for the last 5 years, but they were able to work the match in a fashion that subtly established Yamazaki as Maeda’s peer. Sure, Maeda had the size, but Yamazaki was far quicker and more evasive. He was a dangerous opponent because he could pull a multitude of quick counters into potentially finishing manuevers. Yamazaki, whose kicks had as much snap and zip on them on this night as they ever did, had an early high kick knockdown to establish a potential standup advantage. Maeda was often in control when things finally settled in on the ground, but again Yamazaki drew first blood with a ½ crab that was the first near submission. The match back and forth, but rather than just trading as was too often Maeda’s tendency, they found exciting and surprising ways to exchange the lead. You never knew when one of them was almost beat or they’d fire right back with an attack that was at least the equal of its predescessor. For instance, Yamazaki thrilled the crowd with his best middle kick only to get flattened with a high kick return. Maeda followed up with a chickenwing crossface, but just as Yamazaki looked out of it, he escaped with an ankle lock and reapplied the preestablished ½ crab, putting all his might into stretching the leg, with grimaces akin to that of someone trying to pass a kidney stone. Part of the psychology was that Yamazaki was using Maeda’s shaky knees as an equalizer, so he found more ways to incorporate the ½ crab than anyone else had bothered to imagine. Since Yamazaki was a big underdog, he not only got away with that, he garnered increasing fan support as the legitimacy of his challenge grew. When that still didn’t work, Yamazaki threw all his kicks, going for the big KO after four straight knockdowns. However, Maeda practically took Yamazaki’s had off with Neale kick, and submitted him with a rear naked choke variation. The finish wasn’t the most believable, but they went as far with Yamazaki almost knocking Maeda out as they could. It was basically a war of attrition with Yamazaki getting a bloodly lip. Maeda really went out of his way to put Yamazaki over, allowing him to develop his counter holds as well as slug it out with him. The matwork was really impressive for it’s time, and obviously the standup was no slouch. ****