The Chronological History of MMA

Chapter 10: PWFG Grand Opening 4th 8/23/91 Sapporo Nakajima Taiiku Center

By Michael Betz & Mike Lorefice 4/8/20 |

Greetings one and all!! We at Kakutogi HQ are attempting to make good use of our time in quarantine by continuing to peer into the shrouded haze that is the past in an attempt to better understand our future. When we last left off, Maeda's band of hired misfits, still trying to figure out their brand, gave us a rather lackluster event, but we shouldn't have any such problems here as PWFG has been has been blessed with a rich talent pool right from the start, and if nothing else, appear to have a great main event lined up with Ken Shamrock vs Masakatsu Funaki.

Tonight's event is held within the confines of the Nakijima Sports Center, a multi-purpose facility that was built in 1954, and sadly was the center of tragedy in 1978 when concert goers were unable to contain the excitement of seeing Ronnie James Dio, and a person was trampled to death during a Rainbow concert. Tonight, it will be host to the 4th event from the upstart PWFG promotion, beginning with a bout between Greco-Roman wrestler par excellence Duane Koslowski, and the ever-scrappy Kazuo Takahashi. When we last saw Koslowski, he had a very fine debut against Ken Shamrock where his obvious athleticism and Greco-Roman chops gave his aura an air of gravitas and was enough to overcome any lack of submission and striking skills. After a quick feeling out process, Takahashi shoots in with a nice single leg attempt in which Koslowski unsuccessfully tires to counter with a kimura. It would appear that Koslowski has been spending some time training with Fujiwara's group, working on his submission knowledge, and for that we are thankful. The match was very grappling heavy and played out exactly how you would expect a fight between a catch wrestler and Greco-Roman specialist (absent the striking, of course) to, with Koslowski dominating the standing portions, but Takahashi having more finesse on the ground. While I wouldn't blame anyone for thinking this was boring, I rather enjoyed it, as it set a nice, serious tone to the proceedings. It was a work, of course, but outside of a few flashy slams, there wasn't any gaping holes in the action, and thanks to Koslowski, it came across as a serious endeavor, even if it will be a bit dry for some. Koslowski finished off Takahashi with a standing-switch into a rear naked choke.

Tonight's event is held within the confines of the Nakijima Sports Center, a multi-purpose facility that was built in 1954, and sadly was the center of tragedy in 1978 when concert goers were unable to contain the excitement of seeing Ronnie James Dio, and a person was trampled to death during a Rainbow concert. Tonight, it will be host to the 4th event from the upstart PWFG promotion, beginning with a bout between Greco-Roman wrestler par excellence Duane Koslowski, and the ever-scrappy Kazuo Takahashi. When we last saw Koslowski, he had a very fine debut against Ken Shamrock where his obvious athleticism and Greco-Roman chops gave his aura an air of gravitas and was enough to overcome any lack of submission and striking skills. After a quick feeling out process, Takahashi shoots in with a nice single leg attempt in which Koslowski unsuccessfully tires to counter with a kimura. It would appear that Koslowski has been spending some time training with Fujiwara's group, working on his submission knowledge, and for that we are thankful. The match was very grappling heavy and played out exactly how you would expect a fight between a catch wrestler and Greco-Roman specialist (absent the striking, of course) to, with Koslowski dominating the standing portions, but Takahashi having more finesse on the ground. While I wouldn't blame anyone for thinking this was boring, I rather enjoyed it, as it set a nice, serious tone to the proceedings. It was a work, of course, but outside of a few flashy slams, there wasn't any gaping holes in the action, and thanks to Koslowski, it came across as a serious endeavor, even if it will be a bit dry for some. Koslowski finished off Takahashi with a standing-switch into a rear naked choke.

ML: Realistically, this match was tailor made for Koslowski to dominate, probably in dull Coleman fashion. Through the wonders of worked wrestling though, Takahashi, the amateur state wrestling champion surely at no more than 170 pounds goes right in and takes down the 1988 Olympic wrestler at the highest weight class 130kg (287 pounds, though Koslowski is only a bit taller & there's no way he has close to 100 pounds on Takahashi, there just was no weight class between 100kg & 130kg in the '88 competition). The match followed a similar pattern to Koslowski's debut against Shamrock, with a Greco-Roman takedown or suplex leading to a submission attempt on the mat after a bit of setup, then they'd restart on their feet, but Koslowski was already noticably more confident & diverse. I liked the finish where Koslowski took Takahashi's back when Takahashi tried to counter the bodylock with a koshi guruma, and you figured he was going to do another big German suplex, but instead just pulled Takahashi down into a rear naked choke. Generally, the match wasn't dissimilar from what RINGS was going for on their last event, but while it was also going more for credibility than entertainment, these two were better able to pull it off because they stuck to what they could actually fake believably rather than doing a sad approximation of the match they would be having if they were actually let loose. You could still skip this, but at least it's pretty well done. The execution was good, they just needed more urgency.

Next up is Bart Vale vs Jerry Flynn. This will be only the 2nd professional match from Flynn, having debuted about two years prior in a barbed wire deathmatch for the Japanese FMW promotion. Flynn wound up sticking around the PWFG for a while before migrating to the WWF and then to WCW, working mostly in a midcard capacity. Flynn was a good opponent for Vale, as was similar in style and size/build, which served to hide Vale's main shortcoming, which was that he usually looked like molasses compared to his opponent. Flynn did move faster than Vale, but it wasn't to the point of the matchup straining credulity. This was very striking orientated with plenty of flashy kicks and palm strikes, and surprisingly, this was quite entertaining with Flynn getting the upper hand in the kicking exchanges and Vale dominating the grappling. But just when the match started to build a lot of tension..boom, it just ends out of nowhere with Vale slapping on some kind of modified neck crank/can opener. Entertaining while it lasted, but it ended way too abruptly.

ML: Mr. JF was no Mike Bailey, nor was he one of the few men on the planet that managed to carry RVD and Justin Adequate to good matches like Mr. JL, but the taekwondo black belt had some talent that seemed to be beyond the scope of what the American promotions could envision, so he was mostly an enhancement performer outside of Japan. I was expecting more of a kickboxing match, but perhaps because Vale knew he couldn't match strikes with the longer & quicker Flynn, he looked for the submission finish. This was actually one of Vale's better matches, with the standup having some actual footwork & good palm strikes, and they went into submissions quickly off the takedowns so the ground didn't stall out. Ironically, the kicking was probably the worst part because it was the aspect where it was most obvious that they were holding back. As with the previous match, as a way to favor realism, this had an abrupt submission finish rather than the usual dramatic pro wrestling series of near victories finishing sequence.

Yoshiaki Fujiwara vs Lato Kiroware. At least Fujiwara had the good sense to stick himself in the middle of the card this time, and give Suzuki and Funaki some space to shine. This was a bizarre and strangely hilarious match between the ever rotund Kiroware and the forever aging Fujiwara. Fujiwara always seemed keen on being a jerk when he had someone that couldn't put him in his place, and here we get that, only this time Fujiwara gets to do something that he rarely has been able to do before, and that's use his opponent for a punching bag. Right away, Fujiwara decides that he is just going to keep laying in kicks, and there wasn't anything that Kiroware could really do about it. Kiroware was allowed a few moments of offense, but instead of really laying into Fujiwara for being a jerk, he kept it really light, perhaps not wanting to upset the boss. There wasn't anything good about this match from a technical perspective, but it was a bizarre bit of fun.

Yoshiaki Fujiwara vs Lato Kiroware. At least Fujiwara had the good sense to stick himself in the middle of the card this time, and give Suzuki and Funaki some space to shine. This was a bizarre and strangely hilarious match between the ever rotund Kiroware and the forever aging Fujiwara. Fujiwara always seemed keen on being a jerk when he had someone that couldn't put him in his place, and here we get that, only this time Fujiwara gets to do something that he rarely has been able to do before, and that's use his opponent for a punching bag. Right away, Fujiwara decides that he is just going to keep laying in kicks, and there wasn't anything that Kiroware could really do about it. Kiroware was allowed a few moments of offense, but instead of really laying into Fujiwara for being a jerk, he kept it really light, perhaps not wanting to upset the boss. There wasn't anything good about this match from a technical perspective, but it was a bizarre bit of fun.

ML: Not only is Fujiwara 0-4 in PWFG, but he's arguably had the worst match on every show. Lato certainly didn't help things with some kind of ram headbutt being his big spot, and while I'm not saying Fujiwara should have carried him to a good match, he should have known better than to book him and instead had a real opponent on the roster that he could have had a serious match with. Fujiwara put the shin guards on before tonight's disaster to alert us that he was going to test his foot fighting, and this is why tests are done behind closed doors, and it helps to start with material that's pliable enough. Fujiwara's kicks were just pathetic, he threw high kicks with his knee bent, hook kicks even though he couldn't get his leg up high enough, some kind of running spinning heel kick thing that barely connected to the boob. If his lack of technique wasn't bad enough, he had his usual smirky, clowning attitude going to show the audience he was just screwing around since it was an opponent he could bully (he predictably shrunk from Funaki at the last show).

***********************************Shoot Alert*************************************************

He's back! Yes, the Sultan of Slime has returned, and is ready to ooze all over Minoru Suzuki. When we last saw Lawi Napataya, he gave us an absolutely hilarious classic, and our very first fully planned shoot when he kicked the daylights out Takaku Fuke, while being more greased up than a cholo on an oil tanker. He is facing some stiffer competition in Suzuki, so we'll see if his antics will continue to succeed. The match starts off with Suzuki taking a cautious stance with one arm stretched out, and the other protecting his chin. This stance later became all the rage with striking-deficient BJJ stylists in late 90s, so it's good to see Suzuki blazing a trail here. Despite his caution, Suzuki is taking a few hard leg kicks to his midsection, as he tries to find his timing for a shot.

He's back! Yes, the Sultan of Slime has returned, and is ready to ooze all over Minoru Suzuki. When we last saw Lawi Napataya, he gave us an absolutely hilarious classic, and our very first fully planned shoot when he kicked the daylights out Takaku Fuke, while being more greased up than a cholo on an oil tanker. He is facing some stiffer competition in Suzuki, so we'll see if his antics will continue to succeed. The match starts off with Suzuki taking a cautious stance with one arm stretched out, and the other protecting his chin. This stance later became all the rage with striking-deficient BJJ stylists in late 90s, so it's good to see Suzuki blazing a trail here. Despite his caution, Suzuki is taking a few hard leg kicks to his midsection, as he tries to find his timing for a shot.

Suzuki was finally able to catch one of his opponent's kicks, but Napatays is up to his old tricks, and immediately wastes no time clinging to the ropes for dear life. I must give Napataya a lot of credit for his craftiness, because when they went back to the middle of the ring after a rope-break you could see that Napataya was hesitant to throw another kick right away, so he waited to fire one off until he was back up against the ropes. Sure enough, Suzuki caught the kick, but it didn't matter as he was able to grab a rope just as soon as Suzuki got hold of his leg. Suzuki ate another nasty kick to his thigh before the end of round 1. While the powers that be still haven't put an end to unlimited rope escapes, they at least must have had a talk with Napataya about his grease problem, as his cornermen are on their best behavior this time out, so it doesn't look like we will have any slick shenanigans.

Round 2 starts with Suzuki immediately shooting in on Napataya, and it almost didn't work as Napataya leaped towards the ropes like a wounded tiger. While he was able to get ahold of them, it wasn't enough to stop Suzuki from being able to pry him off and get him down to the ground, where he immediately secured an armbar for the win. Good match, with sound strategy from both fighters. Had Suzuki not been able to pry Napataya off the ropes then he may have been in trouble, as the longer this would have gone on, the harder it would have been for him to obtain the victory. After winning, you would have thought that Suzuki had beat Mike Tyson, the way he was celebrating. Fujiwara got into the act too, running into the ring and hugging Suzuki in what was probably the most emotion he had ever shown up to this point, clearly excited that Suzuki restored the honor of pro wrestlers everywhere from the sneaky grease trap. Apparently, Fujiwara felt vindicated with this experiment as Napataya never returned, and we wouldn't have another shoot like this until the famous meeting between Ken Shamrock and Don Nakaya Nielson.

ML: In just the 2nd shoot in PWFG history, the style has already evolved considerably because Suzuki has clearly studied Napataya's match vs. Fuke (who is in his corner) & thought out how he's going to counteract Napataya's striking attack & takedown "defense". Suzuki was very light on his feet, making kicking defense his first priority, trying to slide back out of range when Lawi threw or check the low kick. What's perhaps more important is that Suzuki wasn't thinking offense with his strikes, but rather staying long & on the outside, using the side kick & occasional body jab to maintain a healthy distance. Because Suzuki wasn't making it easy for Lawi, Lawi grew hesitant, and self doubt continued to fester the more it becomes clear that Suzuki's goal was to get a takedown off a caught kick. Lawi clearly won the 1st round because he's the only one who was landing, but Suzuki shot a double to start the 2nd, and the ref really screwed Lawi by not calling for the break when Lawi was in the ropes. Lawi concentrated on keeping hold of the ropes expecting the ref to do his job rather than doing anything to defend the takedown attempt, and because he was all off balance with 1 leg in the air holding on for dear life, Suzuki was literally able to step back & pull Lawi down on top of him into the center, sweeping as soon as he hit the mat & securing an armbar. Lawi did his best not to tap, but he didn't know how to defend it so he was just taking damage.

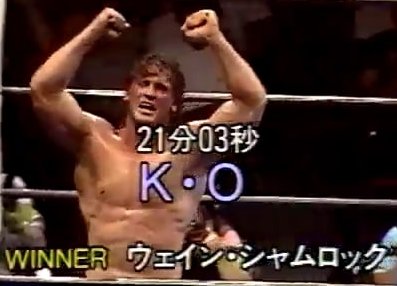

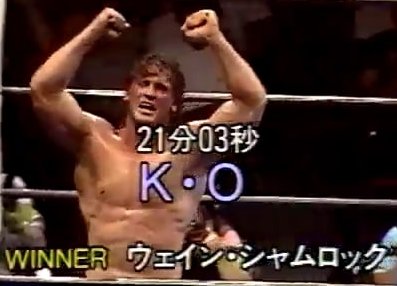

And now. the moment we've all been waiting for: Ken Shamrock vs Masakatsu Funaki. This will be the first time that Funaki will be given a main event here in the PWFG with someone that I expect to really bring out the best in him, and I'm looking forward to it. Funaki wastes no time throwing a kick Ken's way and pays the price by receiving a belly-to-back suplex. Funaki gets up quickly and starts to kick a grounded Shamrock, which causes Shamrock to put his hands behind his neck and start fighting off his back, trying to upkick Funaki with an exchange that is somewhat reminiscent of Allan Goes vs Kazushi Sakaraba 7 years later in PRIDE. This doesn't last long though, as Funaki quickly goes back to the ground, and they go back and forth for a bit, until stood back up by the ref. They immediately go to pounding each other once back on their feet with the best strikes I've seen from Ken so far, and Funaki really putting some velocity behind his kicks. The rest of the fight had it all, strikes, submission attempts, constant jockeying for position, but most importantly, it had an abundance of intensity. They constantly went at each other for 20+ minutes and allowed themselves to be stiff, and it always felt like they were giving their all. Even though the finish looks a bit hokey on paper (Shamrock with a knockout via dragon suplex) it never felt anything less than excellent. One of the best matches we've seen so far.

And now. the moment we've all been waiting for: Ken Shamrock vs Masakatsu Funaki. This will be the first time that Funaki will be given a main event here in the PWFG with someone that I expect to really bring out the best in him, and I'm looking forward to it. Funaki wastes no time throwing a kick Ken's way and pays the price by receiving a belly-to-back suplex. Funaki gets up quickly and starts to kick a grounded Shamrock, which causes Shamrock to put his hands behind his neck and start fighting off his back, trying to upkick Funaki with an exchange that is somewhat reminiscent of Allan Goes vs Kazushi Sakaraba 7 years later in PRIDE. This doesn't last long though, as Funaki quickly goes back to the ground, and they go back and forth for a bit, until stood back up by the ref. They immediately go to pounding each other once back on their feet with the best strikes I've seen from Ken so far, and Funaki really putting some velocity behind his kicks. The rest of the fight had it all, strikes, submission attempts, constant jockeying for position, but most importantly, it had an abundance of intensity. They constantly went at each other for 20+ minutes and allowed themselves to be stiff, and it always felt like they were giving their all. Even though the finish looks a bit hokey on paper (Shamrock with a knockout via dragon suplex) it never felt anything less than excellent. One of the best matches we've seen so far.

ML: This was some ballsy booking, but that's what made it great. PWFG was still determining their top foreigner. Shamrock had been the best performer by a mile, but Vale had been around longer, and after a rocky start in U.W.F., had gone undefeated in 1990 (4-0), even avenging his loss to Yamazaki. Funaki had beaten Vale on PWFG's debut show, but Vale was 3-0 since. Logically, this is where you had Shamrock ascend to the top, especially since Funaki had defeated him on the final U.W.F. show on 12/1/90. However, the timing was tough because Funaki, who had been in the main event of every show and was the top star of the future if not the present, was coming off a crushing defeat to old man Fujiwara, so the normal rebound would be for him to once again defeat Shamrock, confirming the pecking order of Fujiwara, Funaki, Shamrock/Vale, Suzuki. The match was worked like Shamrock was going to ultimately lose, in other words the early portion was about establishing Shamrock was on the level with Funaki by having him take the lead, getting Funaki down with the suplex, winning the kicking battle to score the first knockdown, etc. Funaki's calm & confident demeanor made the match seem closer than it was even during Shamrock's best portions, but by any definition this wasn't Shamrock running away with it, but rather a very competitive back and forth contest where Ken scored the signature shots in between regular exchanges of control as the match progressed were more likely to be won by Funaki. Funaki's patience was something of a negative here, especially when combined with Ken's tendencies to durdle on the mat. Though obviously the underlying problem was the lack of BJJ knowledge from both, the result was a rambling ground affair that was still in the old U.W.F. mode of laying around passively for no reason when the opponent wasn't controlling in a manner that prevented either exploding to counter or to stand back up. Their speed & athleticism was sometimes on display in standup, but because the match was so mat based, I don't feel like it's aged particularly well. It's a good match to be certain, but I remembered it being one of the highlights of the year when in actuality, it's merely a good match, on par with Funaki's matches against Sano but nowhere near Ken's match with Sano, rather than the best stuff of Tamura & Suzuki, who seem miles ahead of the rest of the pack in retrospect. I thought the released Dragon suplex finisher from Ken to score the huge wildly celebrated upset was great because it was in the mold they'd set the whole time, parity but Ken occasionally manages to pull off a great spot. That being said, this was a 21 minute match with a few highlights in between a lot of watching & waiting, honestly more like what we'd come to see from Pancrase though without the modernization of the positions to allow them to get away with it better. ***

Conclusion: Highly recommended. We had a great main event and a historically important shoot, so for those two alone, it's worth watching, but even with the three matches that preceeded it not being mandatory viewing, they were still entertaining, so this was a solid watch start to finish. It will be interesting how things will develop from here. Hopefully Fujiwara will continue to place himself more in the midcard background and leave the spotlight for Shamrock/Suzuki/Shamrock, but that remains to be seen. They could still use a beefier undercard, but out of the three shoot-style promotions they are having the highest quality output, even if they aren't as entertaining top to bottom as the UWFI.

In other news:

The Gracies are at it again, this time with another hilarious puff piece, courtesy of the September '91 issue of Black Belt magazine. Here is the following transcribed article from author Clay McBride: "Unless you've been living in a coma for the last two years, you've heard about the Gracie style of jiujitsu. In an era when many martial artists go out of their way to avoid direct comparisons with rival stylists, the Gracie brothers cheerfully invite doubting individuals to test the combat worthiness of Gracie jiujitsu for themselves.

The Gracies' attitude goes against the popular conception that "it's the fighter, not the style" that determines the outcome of a confrontation. While acknowledging that individuals do exhibit different skill levels, the Gracies refuse to embrace the "all styles are equal" philosophy. They are polite but adamant in their insistence that Gracie jiujitsu is the most realistic, practical, empty hand fighting art in the world.

These Brazilian jiujitsu stylists have further stirred the embers of controversy by issuing their famous "open challenge": they are willing to prove the superiority of their art in "street condition matches" against any opponent, of any style, at any time.

While some may continue to argue the merits of such an invitation on the part of reputable instructors, one fact is undeniable: Rorion Gracie and his brothers are still undefeated. As the calls from challengers dwindle, they have been replaced by invitations by seminar sponsors and requests for lessons from anxious students. Clearly, Gracie jiujitsu is a devastating art. But how do you account for its effectiveness? And how are the Gracies able to transmit the essence of their style to their students so quickly? An examination of the concepts and teaching methods employed by the Gracies provides the answers.

According to Rorion Gracie, the value of a martial art is not predicated solely on the skills of its practitioners. The art itself possess specific qualities which can be used to gauge its effectiveness. Simply singling out individual techniques, however, tells you little about an art. The effectiveness of a style does not lie in isolated movements. To appreciate the sophistication and practicality of a given approach, you must probe the framework in which the techniques are used-the concepts behind the application.

The Gracies contend that their art is superior to other styles, and a cursory examination of their jiujitsu system would seem to reveal several strategic advantages. Following are three of those advantages: Windows and margins. In the real world, opponents seldom fight with the synchronized grace that one observes in sparring sessions between classmates. Men intent on inflicting damage clash with unexpected suddenness. They shift position constantly, refusing to maintain a specific range, and move in wildly unpredictable patterns and broken rhythms.

Punch and kick practitioners, conversely, work within a very specific range of combat. Their "window of opportunity" is very small. If their strike falls short of its target by as little as an inch, it is relatively ineffective. If it lands prematurely, its power may be reduced by as much as 80 percent. Facing an opponent who refuses to maintain a uniform distance, a punch/kick stylist will find it difficult to deliver lethal blows. His dependency on pinpoint precision leaves him with a narrow margin for error.

The Gracie jiujitsu practitioner has no trouble maintaining his chosen range. He simply holds on. Timing his entry, the Gracie fighter either catches his opponent in a moment of overextension, or jams his enemy, smothering his technique. Once the entry has been safely accomplished, the Gracie student secures his hold. There is no need for pinpoint accuracy; any solid grip will serve nicely. Within moments the Gracie stylist executes a takedown, putting his opponent on the ground. From this position, the Gracie fighters "window of opportunity" is unlimited. With his foe held indefinitely at the ideal range, the Gracie practitioner can attempt any number of techniques in rapid succession. His margin of error is enlarged since his enemy is locked in the perfect position, allowing the Gracie stylist the time to apply his techniques for maximum effect.

* Transitions. Martial arts magazines often depict punch/kick practitioners blocking an opponents attack and then scoring with a series of blows. The punch/kick artists retaliation is usually uninterrupted, by the attacker, who stands cooperatively, his initial punch still hanging in space. The illusion created is one of flawless transition on the part of the martial artist. His techniques flow smoothly, one into the next, unimpeded by his frozen opponent.

These "technique in a vacuum" displays, while pleasing to the eye, are misleading. In a real confrontation, the attacker is shifting, dodging and twisting. He is flailing with unorthodox yet powerful punches and kicks; he doesn't just stand by and wait to get hit.

The key to a successful style lies not just in striking techniques, but in the transitions between techniques. Many striking arts do not provide the student with the necessary movements to allow him to neutralize his enemy's aggressions while mounting his own counteroffensive. Any scenario in which an opponent is allowed to move freely while exchanging blows is fraught with peril. It is simple mathematics: the more chances an opponent has to swing, the greater probability he will have to connect.

In Gracie jiujitsu, there is a saying: first you survive: then you win. To put it another way: neutralize your attacker's aggression, then apply your offensive techniques. The Gracie fighter neutralizes his opponent's arms and legs, smothering his technique. Applying simple takedowns, the Gracie stylist robs his enemy of his balance, and thus, his power. Once on the ground, the Gracie practitioner controls his opponent's every movement, manipulating him into a vulnerable position for a finishing technique. As the Gracie stylist maneuvers his enemy toward defeat, he constantly checks any retaliation, neutralizing counterattacks before they develop. By restricting his opponent's movement, he limits his enemy's ability to injure him.

* The familiarization factor. When a punch/kick stylist spars with a partner in class, he maintains a mutually agreed upon distance---one naturally suited to punching and kicking. Exchanging techniques at this specific range, he is lulled into a sense of false security, believing his defensive skills are sufficiently honed to repel an attacker determined to grab him. If, by some implausible "fluke," he did end up on the ground, he believes his eye jabs, groin pinches, or throat strikes, will humble and subdue any foolish "rassler." Of course, the punch/kick artist has never tested any of these beliefs in anything approximating actual conditions. He just knows he is right. Why should he bother to familiarize himself with a style of fighting which poses no real threat? Countless practitioners have passed sweetly into unconsciousness asking themselves that very question.

Unlike the punch/kick stylist, the Gracie student has spent a great deal of time studying the techniques and tactics of his enemy. He respects the tools at his opponent's disposal, but he also knows how to exploit the weaknesses of different styles, because he has actually matched his grappling skills against them. According to the old adage, when two opponents of equal skill and strength meet, the more seasoned man will win. When it comes to combat, the Gracie jiujitsu stylist is the more seasoned man.

It is one thing for a martial artist to possess outstanding skills. It is quite another for him to be able to convey those skills to someone else. The best martial artist does not always make the best teacher. Fortunately for their students, the Gracie brothers also excel at being educators. Their teaching principles, like their art, , are simple, direct and effective, for the following reasons:

One-on-one instruction . While a student may later choose to participate in a group class, his first 36 lessons in Gracie jiujitsu are private. There are no distractions, no idle time. The student has the undivided time of his teacher for the entire class. Under such intense scrutiny, the student's strengths and weaknesses are quickly revealed. The instructor soon familiarizes himself his students nature and psychology, finding the best ways to motivate and challenge the pupil.

* Learning by doing. In Gracie jiujitsu training, the word hypothetical doesn't exist. There are no choreographed exchanges of attack and defense, no step-by-step rehearsels of "appropriate responses" to "possible situations," no one-step sparring. There is only doing. From the moment you step onto the mat until the moment class ends, you are executing throws, takedowns, chokes, arm and leg locks, holds, escapes, reversals, etc. Each technique flows into the next, the specific order dictated only by the moment-to-moment reality of the match. This dizzying stream of moves pauses only when a student reaches a predicament for which he has no response. At that point, the instructor provides another tiny piece of the puzzle and the randori (free exercise) continues. Literally hundreds of movements are compressed into each class, all of them performed in a continues chain.

Another distinct advantage to learning Gracie jiujitsu involves the nature of the techniques themselves. Choking and joint-locking maneuvers are an inherently more humane way to subdue an attacker than smashing his head or ribs. Jiujitsu techniques allow students to practice at realistic levels of power and intensity; they do not have to "pull" their techniques. They can apply increasing pressure until the opponent submits.

Gradually, the pupil is allowed to grapple with fellow practitioners while the teacher supervises. Often this occurs at the end of a student's class, when he is fatigued. Robbed of his strength and endurance, the student must rely on technique alone to overcome his fresh opponent.

* Teaching by example . If a student questions what it is to be a good martial artist, he need look no further than the Gracie brothers. They are committed to seeing that their students learn properly and completely the art of Gracie jiujitsu. They teach with great affection. They do not criticize, they encourage. The do not ridicule, they inspire. Instead of frustration, they offer challenge. And that's a Gracie challenge that everyone can endorse.

If you enjoyed this column, please consider joining the Kakutogi Road Patreon or ordering our Kakutogi Road T-Shirts

BACK TO QUEBRADA REVIEWS

* Puroresu, MMA, & Kickboxing Reviews Copyright 2020 Quebrada *

Tonight's event is held within the confines of the Nakijima Sports Center, a multi-purpose facility that was built in 1954, and sadly was the center of tragedy in 1978 when concert goers were unable to contain the excitement of seeing Ronnie James Dio, and a person was trampled to death during a Rainbow concert. Tonight, it will be host to the 4th event from the upstart PWFG promotion, beginning with a bout between Greco-Roman wrestler par excellence Duane Koslowski, and the ever-scrappy Kazuo Takahashi. When we last saw Koslowski, he had a very fine debut against Ken Shamrock where his obvious athleticism and Greco-Roman chops gave his aura an air of gravitas and was enough to overcome any lack of submission and striking skills. After a quick feeling out process, Takahashi shoots in with a nice single leg attempt in which Koslowski unsuccessfully tires to counter with a kimura. It would appear that Koslowski has been spending some time training with Fujiwara's group, working on his submission knowledge, and for that we are thankful. The match was very grappling heavy and played out exactly how you would expect a fight between a catch wrestler and Greco-Roman specialist (absent the striking, of course) to, with Koslowski dominating the standing portions, but Takahashi having more finesse on the ground. While I wouldn't blame anyone for thinking this was boring, I rather enjoyed it, as it set a nice, serious tone to the proceedings. It was a work, of course, but outside of a few flashy slams, there wasn't any gaping holes in the action, and thanks to Koslowski, it came across as a serious endeavor, even if it will be a bit dry for some. Koslowski finished off Takahashi with a standing-switch into a rear naked choke.

Tonight's event is held within the confines of the Nakijima Sports Center, a multi-purpose facility that was built in 1954, and sadly was the center of tragedy in 1978 when concert goers were unable to contain the excitement of seeing Ronnie James Dio, and a person was trampled to death during a Rainbow concert. Tonight, it will be host to the 4th event from the upstart PWFG promotion, beginning with a bout between Greco-Roman wrestler par excellence Duane Koslowski, and the ever-scrappy Kazuo Takahashi. When we last saw Koslowski, he had a very fine debut against Ken Shamrock where his obvious athleticism and Greco-Roman chops gave his aura an air of gravitas and was enough to overcome any lack of submission and striking skills. After a quick feeling out process, Takahashi shoots in with a nice single leg attempt in which Koslowski unsuccessfully tires to counter with a kimura. It would appear that Koslowski has been spending some time training with Fujiwara's group, working on his submission knowledge, and for that we are thankful. The match was very grappling heavy and played out exactly how you would expect a fight between a catch wrestler and Greco-Roman specialist (absent the striking, of course) to, with Koslowski dominating the standing portions, but Takahashi having more finesse on the ground. While I wouldn't blame anyone for thinking this was boring, I rather enjoyed it, as it set a nice, serious tone to the proceedings. It was a work, of course, but outside of a few flashy slams, there wasn't any gaping holes in the action, and thanks to Koslowski, it came across as a serious endeavor, even if it will be a bit dry for some. Koslowski finished off Takahashi with a standing-switch into a rear naked choke.