Shoot Wrestling 1991 Recommended Matches |

Normally wrestling leagues splintering is bad for the fans because it does little beyond further dilute the talent pool, and while there was a sense of that in 1991, mostly in RINGS since Akira Maeda was ever the loan wolf, the first year of UWF-I, PWFG, & RINGS were characterized by a greater sense of freedom to express your particular brand of martial arts, to have your own focus and quirks without them simply feeling like pro wrestling stabs at marketing. There were a few veterans who changed their style, most notably Masakatsu Funaki & Kazuo Yamazaki moving more toward realism, but predominantly the sudden excess of available roster spots gave wrestlers who had only a handful of matches in the U.W.F., most notably Kiyoshi Tamura, Ken Shamrock, Yusuke Fuke, & Masahito Kakihara or were outright rookies, most notably Volk Han, Hiromitsu Kanehara, Willie Peeters, & Billy Scott the ability to do their thing in a landscape that was very different, and actually evolving. Much of this difference had to do with many of the new wrestlers not being pro wrestlers who were trained in the New Japan dojo, and had worked there before the U.W.F.. At the very least, the natives trained in the U.W.F. showed a more realistic style, working on judo rather than lariats and topes, but it was really the actual martial artists who, in the absense of much legitimate competition, found they could make something of a living doing something that actually utilized their skills to an extent, and didn't leave them feeling embarrassed and ashamed. RINGS was at the forefront of this revolution, bringing in sambo champion Han, bringing back judo silver medalist Chris Dolman and his assortment of Dutch kickboxers and proto MMA fighters, with former bouncer Dick Vrij & Olympic judoka Willy Wilhelm being Maeda's first foes.

Normally wrestling leagues splintering is bad for the fans because it does little beyond further dilute the talent pool, and while there was a sense of that in 1991, mostly in RINGS since Akira Maeda was ever the loan wolf, the first year of UWF-I, PWFG, & RINGS were characterized by a greater sense of freedom to express your particular brand of martial arts, to have your own focus and quirks without them simply feeling like pro wrestling stabs at marketing. There were a few veterans who changed their style, most notably Masakatsu Funaki & Kazuo Yamazaki moving more toward realism, but predominantly the sudden excess of available roster spots gave wrestlers who had only a handful of matches in the U.W.F., most notably Kiyoshi Tamura, Ken Shamrock, Yusuke Fuke, & Masahito Kakihara or were outright rookies, most notably Volk Han, Hiromitsu Kanehara, Willie Peeters, & Billy Scott the ability to do their thing in a landscape that was very different, and actually evolving. Much of this difference had to do with many of the new wrestlers not being pro wrestlers who were trained in the New Japan dojo, and had worked there before the U.W.F.. At the very least, the natives trained in the U.W.F. showed a more realistic style, working on judo rather than lariats and topes, but it was really the actual martial artists who, in the absense of much legitimate competition, found they could make something of a living doing something that actually utilized their skills to an extent, and didn't leave them feeling embarrassed and ashamed. RINGS was at the forefront of this revolution, bringing in sambo champion Han, bringing back judo silver medalist Chris Dolman and his assortment of Dutch kickboxers and proto MMA fighters, with former bouncer Dick Vrij & Olympic judoka Willy Wilhelm being Maeda's first foes.

Having a bunch of rookies has rarely lead to good pro wrestling matches, as they mostly have the same trainer teaching them the same basic holds and counter holds, without much to differentiate them beyond the better athletes and quicker learners rising to the top faster, though probably still getting squashed by whoever the tallest or heaviest stiff in the lot is. Luckily, this was totally not the case in shoot wrestling because there were so many disparate skills and backgrounds on display, honed through years of practicing their more limited and focused arts with a variety of teams, gyms, and coaches. Sometimes rounding out those skills and opening the specialists up enough that they had the striking or submission skills to maintain interest in a game that required them to fight both standing and on the mat took some real effort, but the good news is these guys were, for the most part, already really good in some aspects of the sport that would serve them really well. More importantly, having specialists in all of the legitimate fighting backgrounds other than BJJ really upped the overall level of these skills among their opponents. This was particularly noticeable when it came to amateur wrestling, which seemed to barely exist at the start of the year, but be widespread and decent to good amongst most of the regulars fighters by the end.

There was also refreshingly much less of that overriding pro wrestling philosophy of what you should and shouldn't be doing because everyone wasn't just training the same sequences in the same gym. You were supposed to be realistic, but beyond that the performers seemed to learn from each other, experimenting to try to add new skills to what they'd been doing for years and eliminate the weaknesses they didn't have to deal with in their base arts. Though the new leagues were run by guys who participated in the old one, they surprisingly felt fairly distinct, with UWF-I leaning most toward the flashy end of the spectrum despite having the most shoots with Ohe's regular kickboxing matches & the wrestler vs. boxer shenanigans, PWFG leaning most toward the realistic end of the spectrum, and RINGS being the most martial artist and big show oriented by relying mostly on outsiders with legitimate sports backgrounds. All three leagues ultimately had 1 great, must see wrestler who made the promotion worth following. While obviously it's disappointing that with no interpromotional activity after the U.W.F. split, these guys never fought each other, but the rankings were also very skewed by the odd match making, which saw peculiarities such as Suzuki & Funaki never facing off during their two years in PWFG, while Ken Shamrock faced Suzuki 5 times & Funaki 4 during that stretch. Overall though, this was a really exciting year for quasi shooting, maybe the best year in the sense that they really felt cutting edge and seemed to be advancing the sport because Shooto was so under the radar that these pro wrestling leagues were still as close as most fans got to the real thing, and certainly closer to that concept than what we'd seen in the previous decade.

There was also refreshingly much less of that overriding pro wrestling philosophy of what you should and shouldn't be doing because everyone wasn't just training the same sequences in the same gym. You were supposed to be realistic, but beyond that the performers seemed to learn from each other, experimenting to try to add new skills to what they'd been doing for years and eliminate the weaknesses they didn't have to deal with in their base arts. Though the new leagues were run by guys who participated in the old one, they surprisingly felt fairly distinct, with UWF-I leaning most toward the flashy end of the spectrum despite having the most shoots with Ohe's regular kickboxing matches & the wrestler vs. boxer shenanigans, PWFG leaning most toward the realistic end of the spectrum, and RINGS being the most martial artist and big show oriented by relying mostly on outsiders with legitimate sports backgrounds. All three leagues ultimately had 1 great, must see wrestler who made the promotion worth following. While obviously it's disappointing that with no interpromotional activity after the U.W.F. split, these guys never fought each other, but the rankings were also very skewed by the odd match making, which saw peculiarities such as Suzuki & Funaki never facing off during their two years in PWFG, while Ken Shamrock faced Suzuki 5 times & Funaki 4 during that stretch. Overall though, this was a really exciting year for quasi shooting, maybe the best year in the sense that they really felt cutting edge and seemed to be advancing the sport because Shooto was so under the radar that these pro wrestling leagues were still as close as most fans got to the real thing, and certainly closer to that concept than what we'd seen in the previous decade.

MB: We have witnessed three different promotions all with the same roots, and presumably the same endgames, but with different approaches that have had their pros and cons. The PWFG has been closest to the heart of real shooting, with several performers that have both the talent and desire to push this format closer to their vision of "real" fighting, with the drawback being that they have at times sacrificed entertainment value for realism. The UWF-I, on the other hand, has been the most consistently entertaining of the three promotions by a wide margin, but also the most frustrating, as their insistence on making Nobuhiko Takada appear to be indestructible as well as some of their other booking decisions have shown that they may be the promotion with the most to lose in the next year, as they run the risk of being a flash-in-the-pan with their inability to provide Takada with some real threats to his throne. RINGS has by far had the rockiest start, as Maeda simply had to run this promotion mainly on the sheer strength of his star-power alone, as he is severely lacking any homegrown talent, and his outsourcing almost all of his talent to martial artists with little to no experience in pro wrestling has led to some very uneven results. The upside to this, is that Maeda seems to have the strongest concept in place, and now that Volk Han has arrived, the only direction to go now is up. Another credit to Maeda, is that he is willing to allow himself to lose if it means good business, and honestly he comes across to me as if he wouldn’t mind not wrestling at all, but is forcing himself to do it as it’s the only way to sell tickets and be able to have a television deal in place at this stage in time.

A few of the historical highlights that were witnessed in 1991 include:

The first full-blown MMA fight in the shoot-style era (not counting Shooto) with Takaku Fuke vs Lawi Napataya aAt the 7-26-91 PWFG event.

A shoot fight between Gerard Gordeau and Mitsuya Nagai which took place almost two years before Gordeau was at the inaugural UFC event.

A shoot between Ken Shamrock and Kazuo Takahashi that was short, fast, and brutal. Very entertaining, but perhaps a cautionary tale as Shamrock almost kicked Kazuo’s head off his body and was probably a warning against these kinds of matches from being trusted to happen in the near future.

Shoots between pro wrestlers and legitimate high-skilled boxers. Even though the concept far exceeded the execution, we got to see Billy Scott face a very deadly James Warring in an MMA fight, and while the rules led to a ridiculous outcome, this was a historical snap-shot of protoplasmic MMA.

The birth of Kiyoshi Tamura. He had a brief run the NEWBORN UWF, but was quickly sidelined by an injury given to him by Akira Maeda. The UWF-I has wisely chosen to showcase his talent, but perhaps unwisely not given him as strong as a push as they should have, due to their choosing to groom Gary Albright as the unstoppable suplex machine that will eventually come to blows with Takada. This is unfortunate, as we can see that he is a once in a lifetime performer that not only has endless potential in this style of pro wrestling, but surely has the goods to be effective in real shoots as well. (Though we have not seen him in a real shoot as of yet.)

The debut of Volk Han. Another talent that only comes around once in a generation, this Sambo master would wind up showcasing what was a relatively unknown martial art to the world at large, and gave us a glimpse of new possibilities both in the shoot and shoot-styles.

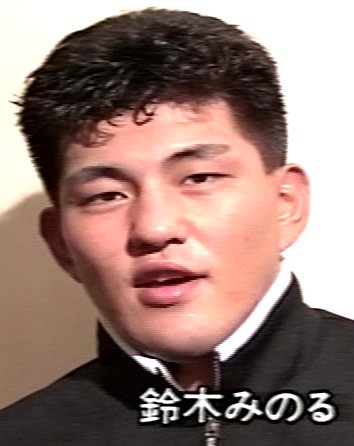

A format that really allowed talents like Minoru Suzuki, Masakatsu Funaki, and Ken Shamrock to flourish and cultivate their skills/identities. Without the PWFG, Ken Shamrock would have probably continued to flounder around in the middle spectrum of American Pro Wrestling, and while there was a chance he could have caught a break in an American promotion with his physique, it probably wouldn’t have come anywhere close to the opportunities afforded to him by being an early star of American MMA. Funaki and Suzuki, on the other hand, probably would have both carved out respectable careers in NJPW or other Japanese pro wrestling companies, but would not have anywhere near the respect or notoriety of having founded the Pancrase organization, and thereby securing their legacies as MMA pioneers.

It remains to be seen what awaits us on the horizon as we venture into 1992, but it is clearly an exciting time as the styles and hearts of each of these promotions have coalesced enough that they each have their separate, yet equally important, identities that are going to blaze the path forward to becoming part of the roots of full blown MMA.

Chronological Reviews of the Best 1991 Shoot Wrestling Matches |

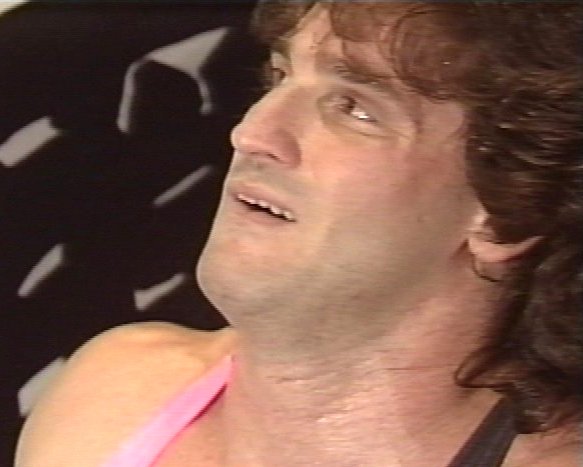

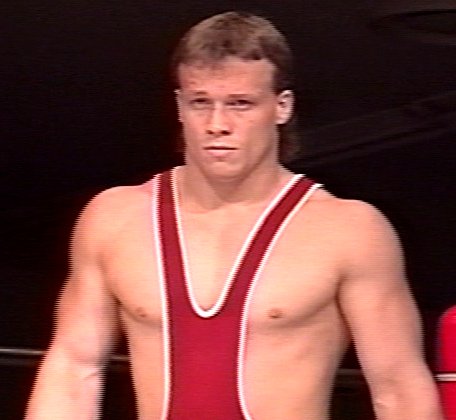

3/4/91 PWFG: Wayne Shamrock vs. Minoru Suzuki 30:00. Suzuki vs. Shamrock is the reason to watch the first Fujiwara Gumi show, an ambitious all out 30 minute draw where their ability to show all the sport is capable of may fall slightly short of their desire to do so, but that desire is so high it's hard to fault them. Being one of the newest and youngest fighters in U.W.F., Suzuki had a hard time seizing the limelight even though he was having strong matches on the undercard, but immediately really came into his own as a regular top of the card performer in PWFG. Fujiwara’s match with Johnny Barrett was definitely more believable, a trend that would quickly be reversed, but it was the younger fighters that Fujiwara gave the spotlight to, particularly Suzuki, who set out to evolve the shooting style by working and countering the holds rather than just lying around and taking rope escapes as many a man had been content to in U.W.F. Structurally, this was still a pro wrestling bout, quite a well built one, at least working up to and in the suplexes and dropkicks that "shouldn't have been there". That being said, their desire to up the realism from the U.W.F. level was quickly, if subtly on display right from the opening sequence where both were hesitant & used small feints to try to set up their strikes, which were really distraction to open up a single leg takedown. There wasn't much striking in the 1st half, which is probably a good thing because Shamrock was often too fake with his hands. However, tensions really escalated in the 2nd half when Shamrock went from a series of mount palms to illegal soccer ball kicks to Suzuki's head, prompting Suzuki - after a break to recover - to come back at Shamrock with a series of short range standing headbutts, which thankfully bore no resemblance to Fujiwara's big windup comedy spot. I would have liked to see them explore the takedown possibilities more rather than revert to the old more Greco style high clinches leading to throws to get the match to the ground, positionally the bout still left a lot to be desired once they hit the canvas as well due to the lack of BJJ, but the grappling was a lot more realistic than much of the U.W.F. stuff because the fighter on the defensive was active, twisting, turning, and rolling to either escape, take the top and/or use their own counter submission. While it wasn't the smoothest match, and it didn't have the best sequences, I was impressed by the active matwork with regular position changes. Most shooters can counter, but one thing that elevated this match above the pack was the intensity and effort they fought with. Everytime you thought one man had made some headway, the other took the advantage at least partially back. The frustration seemed genuine, particularly when Shamrock rope escaped Suzuki’s ankle lock. They just fought so hard throughout the duration of the contest that it never felt as though it would be a marathon, in part because they never stalled, but much of their success was in getting over the concept that they were equals without the usual corniness that has full time draw written all over it. Though the high number of rope escapes wasn't ideal, they did allow for an entertaining ground oriented contest where they were able to keep working hard & threatening one another for half an hour. I appreciated their lack of laziness, not so much in keeping the pace, but the fact that Suzuki, and to a lesser extent Shamrock, understood the importance in putting the effort into their grimacing and contorting to maintain the interest, anticipation, and credibility of what they were doing. They worked some highspots into the submission oriented match such as the overhead belly to belly suplex with a float over and a dropkick, and did some nasty striking in the second half, but the crowd really took to this one because they made their attempts and refusals seem important. By the end of the night, these two had the crowd in the palm of their hands. There was some booing for the draw, but they soon gave the performers a big hand for their exceptional effort. Suzuki was pretty great here, and Shamrock could complement him well enough that the match worked exactly as they hoped, stealing the show with a semifinal draw that propelled them to the main event on 8/23/91.****

3/4/91 PWFG: Wayne Shamrock vs. Minoru Suzuki 30:00. Suzuki vs. Shamrock is the reason to watch the first Fujiwara Gumi show, an ambitious all out 30 minute draw where their ability to show all the sport is capable of may fall slightly short of their desire to do so, but that desire is so high it's hard to fault them. Being one of the newest and youngest fighters in U.W.F., Suzuki had a hard time seizing the limelight even though he was having strong matches on the undercard, but immediately really came into his own as a regular top of the card performer in PWFG. Fujiwara’s match with Johnny Barrett was definitely more believable, a trend that would quickly be reversed, but it was the younger fighters that Fujiwara gave the spotlight to, particularly Suzuki, who set out to evolve the shooting style by working and countering the holds rather than just lying around and taking rope escapes as many a man had been content to in U.W.F. Structurally, this was still a pro wrestling bout, quite a well built one, at least working up to and in the suplexes and dropkicks that "shouldn't have been there". That being said, their desire to up the realism from the U.W.F. level was quickly, if subtly on display right from the opening sequence where both were hesitant & used small feints to try to set up their strikes, which were really distraction to open up a single leg takedown. There wasn't much striking in the 1st half, which is probably a good thing because Shamrock was often too fake with his hands. However, tensions really escalated in the 2nd half when Shamrock went from a series of mount palms to illegal soccer ball kicks to Suzuki's head, prompting Suzuki - after a break to recover - to come back at Shamrock with a series of short range standing headbutts, which thankfully bore no resemblance to Fujiwara's big windup comedy spot. I would have liked to see them explore the takedown possibilities more rather than revert to the old more Greco style high clinches leading to throws to get the match to the ground, positionally the bout still left a lot to be desired once they hit the canvas as well due to the lack of BJJ, but the grappling was a lot more realistic than much of the U.W.F. stuff because the fighter on the defensive was active, twisting, turning, and rolling to either escape, take the top and/or use their own counter submission. While it wasn't the smoothest match, and it didn't have the best sequences, I was impressed by the active matwork with regular position changes. Most shooters can counter, but one thing that elevated this match above the pack was the intensity and effort they fought with. Everytime you thought one man had made some headway, the other took the advantage at least partially back. The frustration seemed genuine, particularly when Shamrock rope escaped Suzuki’s ankle lock. They just fought so hard throughout the duration of the contest that it never felt as though it would be a marathon, in part because they never stalled, but much of their success was in getting over the concept that they were equals without the usual corniness that has full time draw written all over it. Though the high number of rope escapes wasn't ideal, they did allow for an entertaining ground oriented contest where they were able to keep working hard & threatening one another for half an hour. I appreciated their lack of laziness, not so much in keeping the pace, but the fact that Suzuki, and to a lesser extent Shamrock, understood the importance in putting the effort into their grimacing and contorting to maintain the interest, anticipation, and credibility of what they were doing. They worked some highspots into the submission oriented match such as the overhead belly to belly suplex with a float over and a dropkick, and did some nasty striking in the second half, but the crowd really took to this one because they made their attempts and refusals seem important. By the end of the night, these two had the crowd in the palm of their hands. There was some booing for the draw, but they soon gave the performers a big hand for their exceptional effort. Suzuki was pretty great here, and Shamrock could complement him well enough that the match worked exactly as they hoped, stealing the show with a semifinal draw that propelled them to the main event on 8/23/91.****

MB: Fujiwara should get a lot of credit here, as he was willing to put himself in the mid-card and allow some of the younger talent a chance to shine. Here we find a very young Suzuki facing an incredible looking specimen in Shamrock, and it's rather amazing to see that right from the jump, Shamrock was an awesome performer that really shined in this kind of format. One has to wonder if he had jumped back into Japanese pro wrestling instead of the WWF in 1996 how his later career would have turned out, as all he really seemed to get out of his tenure there (outside of a fat stack of cash) was a lot of injuries. While this match was not the smoothest and being a 30 minute draw, it did have its fair share of dead spaces, both fighters did an excellent job of parlaying intensity and frustration throughout. They constantly looked for submissions, even in bad positions, and you could really see an example of a grappling mentality, before the positional thinking of a BJJ influence crept in. The match also had a nice progression to it, as it was mostly submission orientated in the beginning, saving the flashier stuff like a belly to belly suplex, and much nastier striking until later in the match, which gave it natural feel, as if the stakes were getting higher and it was time to pull out all the stops. Though a little dry in spots, a great start to to the new era of shoot wrestling, as well as an insight into the fact that maybe...just maybe.. there was a future paying audience to be found in real fighting.

3/30/91 SWS, UWF Rules: Masakatsu Funaki vs. Naoki Sano 10:23. While Sano's PWFG matches with Suzuki & Shamrock were epic match of the year attempts, this was a fine serious match sandwiched between a bunch of cornball tomfoolery. I liked it, but as with all of Funaki's matches this year, it felt too patient, especially early on. It was wrestled as though they were going 20 minutes, which is what would have happened had it taken place in PWFG, until they packed virtually all the action into the final 45 second explosion. A good and interesting match, but hardly the classic they were capable of. ***

3/30/91 SWS, UWF Rules: Masakatsu Funaki vs. Naoki Sano 10:23. While Sano's PWFG matches with Suzuki & Shamrock were epic match of the year attempts, this was a fine serious match sandwiched between a bunch of cornball tomfoolery. I liked it, but as with all of Funaki's matches this year, it felt too patient, especially early on. It was wrestled as though they were going 20 minutes, which is what would have happened had it taken place in PWFG, until they packed virtually all the action into the final 45 second explosion. A good and interesting match, but hardly the classic they were capable of. ***

4/1/91 SWS: Masakatsu Funaki vs. Naoki Sano 23:42. This was at least epic in length, though not in quality. They started stronger than their previous bout with a lot of standup, even though it was initially a bit too much toward sparring. Things picked up with Funaki dropping Sano with a palm strike, and it was almost a short night for Naoki, as they redid the finish from 3/30, but this time Sano was more prepared, and thus able to defend the armbar. From here, the standup was more aggressive, but again, it never really seemed like Sano had anything to truly threaten Funaki. Sano had some top control, and could land a damaging strike now and then, but Funaki had more speed and more technique, even a low blow couldn't slow him down for long. This was definitely the better match of the two, as it was not only much better developed, but also got going a lot quicker. However, it was almost as if Funaki was too good for the match to approach its potential. This should have blown Sano vs. Shamrock away, and while the striking was certainly better, it felt like Sano had answers for Shamrock and could win that match, whereas this one he'd really have to just get lucky. Still, a good match that was light years ahead of the rest of the show. ***

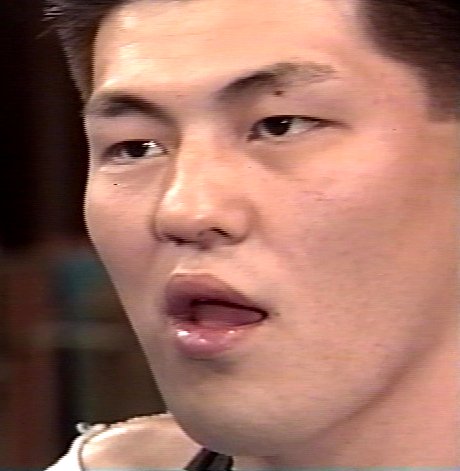

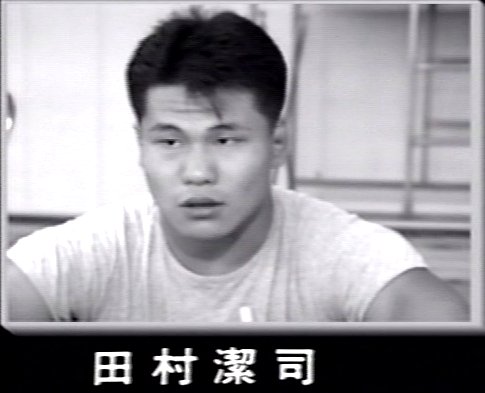

5/10/91 UWF-I: Kiyoshi Tamura vs. Masahito Kakihara 14:16. Giving their brightest new lights the opportunity to usher in the new era of shootfighting was a great way to start the new promotion. Tamura and Kakihara did themselves and the promotion proud with a crisp and energetic contest. As is always the case with the early shoot style, the standup was a lot more credible than the mat because kickboxing and muay thai were well established sports, while judo and amateur wrestling had their place in the Olympics, but had never been deemed entertaining enough to be ticket selling sports, and thus the fighters were probably less encouraged to fully utilize or really even develop those styles. Instead, they just incorporated the spectacular end game of the throw rather than teaching the audience to be patient while they set one up. When all else failed, they could always get the bout to the canvas with a good old fashioned leg scissors, as Kakihara did here. This was a good match but obviously nowhere near their best work. One has to keep in mind that Tamura was out from 10/25/89 when sloppy Maeda accidentally fractured his orbital with a knee until the final UWF show on 12/1/90. Then there were no shows for the next 6 months as everyone reorganized, so this was only the 7th match of Tamura's career, which still put him 2 ahead of Kakihara, who debuted on 8/13/90. Though these two have always been linked because of their age and popularity, at this point they weren't the best matchup for one another because their strengths differed considerably. Both are talented enough to offer things in the other man's realm, but for the most part the match played out logically, with Kakihara trying to avoid grappling and Tamura trying to avoid striking though there was one truly standout exchange and Tamura did considerably more striking than in any of his other matches this year. Overall though, this layout really hurt the match because the development of the sequences is what makes Tamura shine and stand apart, while this was basically just a back & forth spotfest. What Kakihara had right from the outset was a very infective, wild passion. He may not have been cut out for real fighting, but if he were, he would have been one of those high risk all action fan favorite fighters who goes for bonuses and finishes, one way or the other, rather than just trying to win safe. Kakihara certainly had his routine, but he may have been the only wrestler that, no matter how many times you saw him engage in those rapid fire palm barrages or wild kicks, you still felt his match was legitimately getting a bit out of control. That out of control nature, combined with their blistering speed, really elevated the believability of his strikes, as throwing fast as you can combos is much more intense and believable than the usual loading up on 1 strike, which everyone can see coming a mile away and clearly witness the faults of. Tamura was a good compliment to Kakihara because he could ground him just enough that they could strike a balance between an out and out highlight real and a technical fight. Overall, this was much more toward Kakihara's style though, and a bit too overeager. ***

5/11/91 RINGS: Willie Peeters vs. Marcel Haarmans 10:51. Peeters was the most interesting of the original roster because he more or less really went at it, and his matches were extremely intense, out of control, and sometimes baffling because of that. None of his matches this year were straight up shoots, but they felt less planned than what most of his peers were doing. Peeters might not have been actively trying to knock Haarmans out, but he wasn't really pulling his strikes either, which made for an odd constrast given Haarmans was pulling his, and I kept waiting for Haarmans to complain about the way Peeters was laying into him. What's actually more interesting though, and makes the match look very much ahead of its time, is the lack of cooperation on the throws and various attempts to get each other down, resulting in a style where both guys exploded and whatever happened, happened. Seemingly Peeters would sort of cooperate by not specifically resisting the lockup or immediately trying to get back to his feet in the grappling, allowing Haarmans to toy around with crabs, but he wouldn't necessarily cooperate with the throws and transitions. There was a lot of flash though, mostly from Peeters, with spinning kicks and belly to belly suplexes since Haarmans was much more obliging, but they both made each other work for things & didn't sacrifice the essence of the fight for entertainment value. ***

MB: Peeters was a master of general jackassery for most of his career, but at least he was entertaining throughout it all. This match was bizarre, as Haarmans was trying to be a professional in the ring and put the appropriate amount of force behind his strikes, but Peeters seemed to be content in doing whatever he felt like. He wasn't completely shooting, as he would allow Haarmans some time to work for a submission, but he was definitely taking liberties by laying into Harrmans with strikes that were certainly much stiffer than Haarmans was bargaining for. I wound up being surprised that Haarmans put up with this, as I was expecting him to either complain to the ref, or start shooting on Peeters, but he stayed level-headed throughout, which only further served to illustrate that Peeters was a jerk. Still, this served as an intriguing example of what could be achieved in this style, when there is a legitimate amount of non-cooperation, which would later be fully realized by some of the PWFG matches later in the year.

5/16/91: Naoki Sano vs. Wayne Shamrock 26:15. Suzuki's match with Shamrock on the previous show was considerably better because he has a lot more ability to both lead & react, and is by far the most creative of the three, but while Shamrock was forced to initiate a lot more here, he was able to maintain his patience & do a good job, with Sano bringing some good things to the match. Sano was the better standup fighter, landing some solid low kicks early (though he didn't really attempt to follow them up) and a lot of good openhand shots that helped force Shamrock into a more grappling centric performer. The basis of the match was ultimately Shamrock controlling with superior wrestling, forcing Sano to make things happen. It's unfair to compare a shoot debuting Sano to Suzuki in the style Suzuki has been training in for 2 years, but in any case Sano obviously wasn't totally ready to match his ability in junior heavyweight action yet. He was good in the striking exchanges and had some submissions in his arsenal, but most of his transitions & counters would have taken the bout to a more puroresu place, and he was trying not to go there too often. While the bout had the long match vibe too it throughout, emphasizing position changes on the mat over finishing opportunities, that was mostly okay because they kept the credibility a lot higher than it would have been, even if things meandered a bit more. I don't want to make it sound as if credibility was near the top of their priorities, Sano got a takedown with a jumping DDT and a knockdown with a jumping spinning heel kick that mostly missed, while Shamrock did a few of his suplexes, but they built the match up well to these meaningful highlights, and didn't lose the plot when they failed to finish with them. Sano began to press in the standup, with Shamrock happy to get involved in a flurry because it would help him grab Sano & land his clinch knees, which tended to result in the bout hitting the mat one way or another. The finish didn't really work for me because by continuing to exchange the openhand strikes on the inside, Sano somehow getting behind Shamrock when he missed one of these short shots without much hip turn was pretty clunky. Nonetheless, Sano did a released version of one of his wrestling favorites, the Dragon suplex, turning into the wakigatame for the finish. Definitely a good match, you could certainly argue very good, but my memory of it was better than it looks to me today. ***1/2

MB: The first few minutes start off with the fighters feeling each other out on the ground, with Ken ever looking for a leg attack entry. This is interesting to watch from a modern vantage point, as it was clearly by people that weren't in the BJJ mentality of "position over submission." Sano will attempt to place Ken in a bad position, and as soon as Ken is able to reposition himself, he instantly goes for the attack, which was the mindset of Catch Wrestling. Both men jockey back and forth on the ground for a while, with both trading Kimura, toe hold, and choke attempts. This goes on for a while, until Shamrock is able to secure a rear naked chock, thus forcing a rope escape from Sano. They get stood back up and escalate the entire affair with some stiff palm strikes, and nasty knees from Sano. Everything is looking very snug and believable until a momentary show of flashiness takes place with a jumping DDT from Sano. This didn't really amount to a whole lot, as Shamrock quickly reversed his position by applying a hammerlock variant into another rear naked choke attempt and rope escape. After trading a couple of kicks, Shamrock hits an explosive Northern Lights suplex into a Kimura, which is super impressive looking, but admittedly fake as all get out. This surprisingly didn't accomplish much as Sano was right back up with some more kicks and managed to score a knockdown against Shamrock. Shamrock gets back up and they continue to trade submission attempts, but one thing I'm starting to notice is that this has a great back and forth feel, without the sometimes-scripted feeling that a RINGS match would give off. The limited rope-escape format of RINGS could add a lot of drama to a match, but often produced matches that felt very formulated. The PWFG approach of unlimited rope escapes allows for a much more organic match to take place, although can also lead to bouts of meandering if not done correctly. The match continues to seesaw all the way until the 25:00 min mark, when everything culminates into an explosive crescendo, as both men give everything they have into knees/palm strikes towards one another. Sano gets behind Shamrock and hits a Dragon suplex followed by a straight armbar for the win. While not perfect, this was a great match that really showcased the new and uncharted territory that this style could deliver. It was fairly credible, outside of a few highspots and Shamrock's striking needing to be a bit stiffer. Still, this was a glimpse of some of the magic to come, and Sano proved to a perfect foil to the powerhouse that was Ken Shamrock.

6/6/91 UWF-I

Makoto Ohe vs. Rudy Lovato 5R. Kickboxing never had a history of worked matches, so lucky for us, the powers that be had no problem putting on a match with legitimate, high level all out lightning speed combos before their series of flatfooted, pulled palm strikes. UWF-I's foot fighting division was essentially just Ohe, but Ohe was both an exciting little fighter as well as a good one who had been champion in Shootboxing, and while in UWF-I, went on to win the ISKA World Super Lightweight Title. Tonight's opponent was "Bad Boy" Rudy Lovato, a journeyman boxer from Albuquerque who once had one of his fights stopped when a rowdy fan pelted him with a soda bottle. Though he won that via unanimous decision, and went on to claim the vaunted Canadien American Mexican Jr. Middleweight title, he wound up 21-40-4 in a 21 year career. That being said, he was a legitimately good, multi-belt champion in the less lucrative and largely undocumented art of kickboxing, and he truly ushered in UWF-I's new division with a memorable fast pace war. The action in this contest was pretty insane because they had no regard for defense to the point that early on they often didn't even wait for each other, simultaneously throwing their lengthy combos. Lovato had much better hands, and with Ohe not looking to defend (the only way this match slowed down is that he often grabbed a clinch to bring knees), it was amazing how many shots in a row he could land, often even with the same hand. Ohe was definitely the more diverse striker though, and the basic problem for Lovato is he couldn't match Ohe's kicks, which were shredding his legs. Even though Lovato scored a knockdown in the 1st catching Ohe coming in with a right straight, he was almost forced to pat on the inside when Ohe initiated the clinch rather than fighting hard to keep enough distance to land his damaging hooks & uppercuts because Ohe would answer those with debilitating leg kicks. Lovato did his best to slow Ohe down, really digging the body hooks in as his best answer for the low kicks. One of the things that made this fight so interesting is Lovato was winning the short term wars, he had the knockdown and was the one who would stun Ohe from time to time, but Ohe was winning the long term battle because his offense was slowly shutting Lovato down. Given Lovato was based in the US, it's likely he had little to no experience with kicks below the waist and knees being legal, but in any case he wasn't checking enough of the kicks or was telegraphing his check, which would allow Ohe to just bring the kick up to the thigh. While Lovato's right leg was worse, both were ready to go early in the 3rd, and Ohe finally took this round then got a low kick knockdown to start the 4th. Lovato switched things up going to something of a side stance and throwing a couple side kicks, which forced Ohe to close the distance, and when he clinched, Lovato backed & punched his way out instead of accepting it, nearly dropping Ohe with a right. Though they battled it out late in the round, fatigue was finally setting in, and Ohe never truly recovered. The 4th was a great round, with Lovato now holding his own at range in punch vs. kick exchanges, but Ohe no longer had the forward drive in the 5th, so Lovato was finally able to dominate with distance boxing. Though this was the only legitimate fight on the card, it also told the best story, and it was fun that the tale it seemed to be telling was actually reversed, with Lovato's volume & body punching winning the attrition war & allowing him to mostly use his power punching late even though he no longer had much ability to move had Ohe still been able to press him. Lovato should have won a decision, but UWF-I uses an odd scoring system instead of blind mice, and while Lovato finished up 29-27, that's not a big enough margin for a victor to be declared. Great match.

MB: In the pre-match interview, Rudy explained that he had been doing his usual Kickboxing training, but to prepare for this match, he was really working on how to use knees. Such a thing seems elementary in our post K-1/Muay Thai familiar world, but in 1991, the only time an American was likely to have to deal with low-kicks, knees, or clinch fighting was when he fought abroad. Immediately both fighters start tearing into each other with no let up. After a steady barrage from both men, we begin to see that Lovato's seeming lack of experience with the Thai style of fight is becoming a chink in his armor. Ohe was able to really take advantage of the clinch and work a steady stream of knees into his opponent, which mostly garnered the response of Rudy putting up his hands and having the ref break it up. By the time the 2nd round was underway though, Lovato had seemingly come up with an answer, and started tirelessly working stiff/short uppercuts to punish his clinch-happy adversary. Rudy wasn't out of the woods entirely, as Ohe continued to spam Lovato with low kicks that he was ill equipped to check properly. After a while, the pattern of the fight started to shift into what was basically a battle of foot vs. fist, with Lovato having the edge in boxing skills, and Ohe with the experience with low-kicks and knees. That's not to say that there weren't plenty of punches from Ohe, or kicks coming from Lovato (there were), but we did wind up getting a great snapshot of the disparity between Western/Eastern styles of kickboxing from this era. Round 3 had hardly started when Ohe delivered a devastating thigh kick to Lovato, which almost took him out of the fight for good. Somehow Rudy managed to hang on, but after this he was forced to rely on his boxing, as his legs were pretty much out of the equation. To his credit, Lovato continued to chip away with uppercuts, when Ohe wisely shoved his opponent into the corner and delivered a straight punch that would have resulted in a 10-count, but when Lovato fell, his leg fell in-between the ring ropes, which caused the ref to consider it a slip instead. Rudy spent the rest of the round just surviving and hoping the bell would ring. Ohe starts the 4th with a kick into Lovato's midsection that leads to a knockdown. Lovato was able to get up quickly though, only to suffer more punishment for his efforts. All seemed to be lost, when miraculously Rudy was able to turn the tide by throwing a couple of perfectly timed sidekicks into Ohe's solar plexus as he was charging in. It would figure that the most American of all kickboxing staples, the sidekick, would be the key that could potentially unlock victory, and makes me wonder if he should have been using this technique a lot earlier in the fight. The rest of round 4 and round 5 saw more of the same, Lovato continuing to throw combinations, but eating nasty kicks from Ohe. Amazingly, at the end of round 5, it was Ohe that was barely walking, and needed help back to his corner. The fight was declared a draw, and a great fight it was!

Kiyoshi Tamura vs. Tom Burton 9:08. The most overachieving match of the UWF-I. The first minute of this fight alone had more compelling moments than the entirety of Takada's feeble effort to pull anything out of Burton in the debut show's main event. Tamura was actually interacting with Burton, and that was making it a riveting, high quality match as they kept pulling unconventional answers. Right from the get go we saw not simply a basic a striker vs. wrestler fight, but that Burton had knees to answer Tamura's kicks, while Tamura had a roll to counter Burton's takedown and take the top himself. The whole match was based on this sort of back & forth where one discipline of martial arts provided the answer to another. Look, Burton may not be the tightest or most agile worker out there, but Tamura was fantastic here, crafting a match that was intense, explosive, exciting, unpredictable, and creative, and to his credit Burton was consistently able to go outside of the box to answer him. This was on the short side, but that was really a necessity given Burton. Even if Burton was a little sloppy and awkward in his slams and transitions, no one would have expected this bout to often be shockingly excellent. It was really exciting seeing Tamura demonstrate what he could truly do for the first time, and get such a match out of Burton, whose career is practically only memorable for the matches against Tamura. As such, I'm ranking this at in the UWF-I top 5 of the year over a couple other solid contenders, Scott vs. Anjo and the 11/7/91 tag, that could possibly be marginally better in the grand scheme of things, but at the same time didn't make nearly as much of an impression upon me. ***1/2

Yuko Miyato vs. Kazuo Yamazaki 11:00. Yamazaki is such a subtly great performer. Tamura, Takada, & Han were more flashy, but because of that they often just jumped to the action & kept it coming, whereas Yamazaki set things up and did many little things that were ahead of his time to make his matches credible. Though he doesn't have a specific background in karate or kickboxing (he was one of 3 members of the high school judo team), his mentor was Satoru Sayama, and he used to teach in Sayama's gym during the original UWF days. Yamazaki was willing to start slow, using little hand fakes, leg lifts, quick hip twitches to keep Miyato guessing when and how he was coming. Yamazaki seemed to take over when Miyato ducked a right hook kick, but then ate a left kick to the liver. However, Miyato answered with his one big weapon, the rolling solebutt. I like Miyato, but lack of creativity was really his big problem, in that he really seemed content to be the undersized guy who could hit a couple home runs, though as this is fighting rather than baseball, that style was more equivalent to having a puncher's chance. The match was just designed to put some heat back on Yamazaki since he lost to Anjo on the 1st show, but Yamazaki knew how to keep Miyato in it while gaining incremental advantages. Yamazaki's focus was on destroying Miyato's legs, and he was targetting them with most of his kicks & submissions, without forcing things. Miyato's kick to break Yamazaki's Achilles' tendon hold was both the shock & highlight of the match, it was almost as if he just boosted his butt off the canvan into a sort of ground enzuigiri. Increasingly though, he had no defense for Yamazaki's low kicks, and ran out of points getting knocked down by them. ***

MB: Yamazaki always brought great psychology to his matches, used proper feints and footwork, and had a demeanor that suggested he was in a real fight, which is sadly a rarity in pro-wrestling. This match breaks from the high-octane approach of the nights prior bouts, with an almost subdued, methodical performance from both men. They spend several minutes feeling each other out, with Yamazaki coming across as a cat waiting for the perfect moment to pounce, whereas Miyato seems to know this, and is cautiously looking for an answer. About halfway into the bout, Yamazaki just decides to start kicking Miyato into oblivion, which forces a rope escape, and sets a new tone for the match. Miyato returns the favor, and in the course of these exchanges we learn the true counter to an Achilles' hold, which is simply to kick your opponent in the head with your free leg. So simple, and yet so elusive. Well played, Miyato. This was Miyato's final act of defiance, as Yamazaki proceeded to use him for target practice for the rest of the match, effective kicking him to shreds. Both myself, and the crowd at the Korakuen Hall enjoyed every glorious min of it, as truly, Yamazaki does not seem capable of turning in a bad performance.

7/3/91: Kiyoshi Tamura vs. Yoji Anjo 17:35. The man who will advance the worked game to its highest level arrives here, in just his 9th pro match. As the leading light of the next generation of shooters, the guys who debuted in one of the worked shoot leagues rather than being trained in the New Japan dojo, Tamura at least feels a lot more like a catch wrestler than a pro wrestler, and this is the most progressive match we've seen so far. Tamura may not yet be reaching new levels of believability, but as by far the most explosive grappler in shoot wrestling, he's at least expanding the boundaries of what crazy things you can get away with and how entertaining you can be without simultaneously testing the groan factor. Kakihara has more hand speed, but isn't nearly as slick or well rounded, certainly can't adjust & transition on the mat or maneuver his body the way Tamura can. Tamura is just such an amazing mover that watching him do a simple pivot to avoid a takedown, much less his more spectacular movements, is usually more exciting than watching the juniors do their gymnastic counters. There was an amazing spot where Anjo was not so much trying to set up a guillotine but just to control Tamura with a front facelock, however Tamura did this crazy counter where he bridged backwards just to get low, then when he had separated Anjo's clasp by getting under it, he changed the direction of his explosion entirely & somehow took Anjo's back into a rear naked choke. I want to say that Tamura does things that nobody can do, and while that's probably the case with this particular maneuever, generally it's more accurate to say he just does them so fast he catches the viewer (if not also the opponent) off guard, whereas with most anyone else you could see these moves coming and they might even look clunky because they aren't fast enough to disguise how they are being done and/or the cooperation or lack of opponent's reaction they entail. This was really a different match for Anjo because Tamura was already such a tidalwave that, when he had a full tank, Anjo was just reacting to him desperately trying to keep up. Anjo is known for his cardio, and normally is prone to more durdling given he's almost always in the longest match on the card, but you could see early on that when Anjo thought he was safe, the next thing he knew Tamura had his back, so Anjo could never relax & had to be proactive. While this started off sort of like a junior heavyweight match, rather than slowing after the early fireworks, it was arguably even faster & more explosive once they shifted from throws into the matwork, with some great twists, turns, and rolls to escape the opponent's submission or counter into their own. The story of the match was early on Tamura would gain the initial advantage with his blinding speed, but Anjo had a massive experience advantage, and by being the smart veteran who focused on working the body to slow Tamura down, he was able to not only get into the match, but eventually take over due to his superior striking offense & defense. As the match progressed, it wasn't so much Tamura doing circles around Anjo, but rather Anjo making Tamura pay to get the match to the canvas. It's always been a point of pride for Tamura to find the answers to what the opponent is doing and generate offense out of defense rather than grabbing the ropes, though obviously he'd get much better at this as his career progressed. Despite Tamura already being the best defensive grappler in the worked game & making a ton of great squirmy counters to save himself, there's quite a few rope escapes as Tamura is a massive underdog given Anjo has been around since '85 and is now hitting his peak. However, by doing everything he can to avoid the rope escape, Tamura generally elevates the moves that actually require them to the intended level, in other words rather than just gaming the system as we'd see the strikers do in the few actual shoots this year, these felt like moves that were deep enough they would have won had they been caught in more advantageous ring position. They exchanged advantages on the ground a lot, but one of the big differences is while Tamura would look for the immediate payoff with a submission, for instance a lightning go behind into a rear naked choke, Anjo was confident in his ability to win the attrition battle, and thus happy to take any opportunities for damage, for instance burying knees in Tamura's face. Anjo was also happy to put the youngster in his place, so when Tamura would get too overexuberant, fiesty, or nervy, Anjo would do something within the rules but slightly dickish or excessive such as the knees to take him down a peg. Tamura was already really over, and the fans would go nuts when he appeared to have a chance to win, for instance the half crab after ducking Anjo's leg caught reverse enzuigiri. He didn't have too many of those chances though, as most of his highlights were early on, and it became more of an uphill battle as Anjo wore him out beating up his midsection. That being said, it's not as if Tamura wasn't getting submissions, but Anjo was defending them better in the story sense of finding ways to get out of trouble without losing points. Still, Tamura was so impressive the match seemed a lot closer than it was on the scoreboard, which mostly isn't that relevant given points are a resource as long as you still have 1. Though Tamura's performance was the awesome one, Anjo really did a great job of both following him as well as filling in around him, and deserves a ton of credit as well. ****1/2

7/3/91: Kiyoshi Tamura vs. Yoji Anjo 17:35. The man who will advance the worked game to its highest level arrives here, in just his 9th pro match. As the leading light of the next generation of shooters, the guys who debuted in one of the worked shoot leagues rather than being trained in the New Japan dojo, Tamura at least feels a lot more like a catch wrestler than a pro wrestler, and this is the most progressive match we've seen so far. Tamura may not yet be reaching new levels of believability, but as by far the most explosive grappler in shoot wrestling, he's at least expanding the boundaries of what crazy things you can get away with and how entertaining you can be without simultaneously testing the groan factor. Kakihara has more hand speed, but isn't nearly as slick or well rounded, certainly can't adjust & transition on the mat or maneuver his body the way Tamura can. Tamura is just such an amazing mover that watching him do a simple pivot to avoid a takedown, much less his more spectacular movements, is usually more exciting than watching the juniors do their gymnastic counters. There was an amazing spot where Anjo was not so much trying to set up a guillotine but just to control Tamura with a front facelock, however Tamura did this crazy counter where he bridged backwards just to get low, then when he had separated Anjo's clasp by getting under it, he changed the direction of his explosion entirely & somehow took Anjo's back into a rear naked choke. I want to say that Tamura does things that nobody can do, and while that's probably the case with this particular maneuever, generally it's more accurate to say he just does them so fast he catches the viewer (if not also the opponent) off guard, whereas with most anyone else you could see these moves coming and they might even look clunky because they aren't fast enough to disguise how they are being done and/or the cooperation or lack of opponent's reaction they entail. This was really a different match for Anjo because Tamura was already such a tidalwave that, when he had a full tank, Anjo was just reacting to him desperately trying to keep up. Anjo is known for his cardio, and normally is prone to more durdling given he's almost always in the longest match on the card, but you could see early on that when Anjo thought he was safe, the next thing he knew Tamura had his back, so Anjo could never relax & had to be proactive. While this started off sort of like a junior heavyweight match, rather than slowing after the early fireworks, it was arguably even faster & more explosive once they shifted from throws into the matwork, with some great twists, turns, and rolls to escape the opponent's submission or counter into their own. The story of the match was early on Tamura would gain the initial advantage with his blinding speed, but Anjo had a massive experience advantage, and by being the smart veteran who focused on working the body to slow Tamura down, he was able to not only get into the match, but eventually take over due to his superior striking offense & defense. As the match progressed, it wasn't so much Tamura doing circles around Anjo, but rather Anjo making Tamura pay to get the match to the canvas. It's always been a point of pride for Tamura to find the answers to what the opponent is doing and generate offense out of defense rather than grabbing the ropes, though obviously he'd get much better at this as his career progressed. Despite Tamura already being the best defensive grappler in the worked game & making a ton of great squirmy counters to save himself, there's quite a few rope escapes as Tamura is a massive underdog given Anjo has been around since '85 and is now hitting his peak. However, by doing everything he can to avoid the rope escape, Tamura generally elevates the moves that actually require them to the intended level, in other words rather than just gaming the system as we'd see the strikers do in the few actual shoots this year, these felt like moves that were deep enough they would have won had they been caught in more advantageous ring position. They exchanged advantages on the ground a lot, but one of the big differences is while Tamura would look for the immediate payoff with a submission, for instance a lightning go behind into a rear naked choke, Anjo was confident in his ability to win the attrition battle, and thus happy to take any opportunities for damage, for instance burying knees in Tamura's face. Anjo was also happy to put the youngster in his place, so when Tamura would get too overexuberant, fiesty, or nervy, Anjo would do something within the rules but slightly dickish or excessive such as the knees to take him down a peg. Tamura was already really over, and the fans would go nuts when he appeared to have a chance to win, for instance the half crab after ducking Anjo's leg caught reverse enzuigiri. He didn't have too many of those chances though, as most of his highlights were early on, and it became more of an uphill battle as Anjo wore him out beating up his midsection. That being said, it's not as if Tamura wasn't getting submissions, but Anjo was defending them better in the story sense of finding ways to get out of trouble without losing points. Still, Tamura was so impressive the match seemed a lot closer than it was on the scoreboard, which mostly isn't that relevant given points are a resource as long as you still have 1. Though Tamura's performance was the awesome one, Anjo really did a great job of both following him as well as filling in around him, and deserves a ton of credit as well. ****1/2

MB: Not even a minute and half into this and we already have stiff strikes, a slam, a double leg takedown, and a beautiful O-Goshi throw from Anjo. The pace never lets up either, as all sorts of position changes and submission attempts from Anjo occur, before Anjo is finally able to force a rope escape due to catching Tamura in a straight armbar. A beautiful sequence followed where Anjo attempted a flying armbar to which Tamura counters with a cartwheel, which is absolutely genius, and shows that we are witnessing something that is truly far ahead of its time. The rest of the bout was filled with a tidal wave of transitions, submission attempts, and passionate striking, all done at breakneck speed. The fight finally ended when Anjo was able to secure a single leg crab, but to his credit, was able to quickly torque it in a way that actually came off as somewhat credible. While this fight won't hold up on the believability scale to a modern MMA audience, due to the tempo and lighting fast fluidity, it was still truly something special, and may so far be the best glimpse of what both this style of pro-wrestling has to offer, as well as what REAL fighting may have to offer. Up to this point, it was probably just a given in the pro-wrestling world that you had to have Irish whips, clotheslines, and hokey submissions to create a product that people would want to see, but here we have wrestlers actually moving like 3-dimensional fighters, (or at least catch-wrestlers) and showing that there may be something after all to shooting.

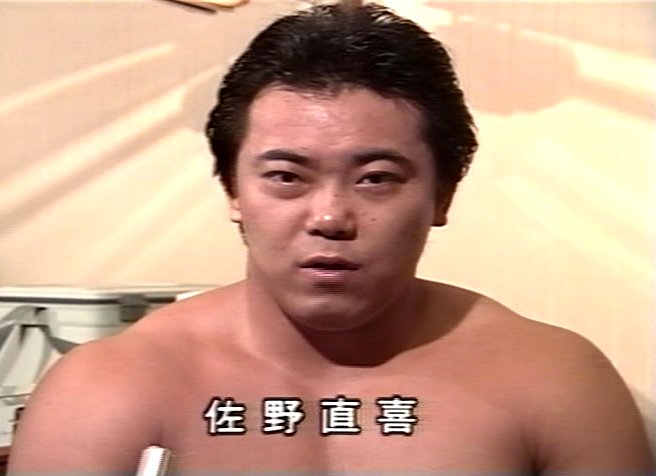

7/26/91: Minoru Suzuki vs. Naoki Sano 30:00. The previous two high end PWFG matches were Shamrock vs. Suzuki and Shamrock vs. Sano, but with Suzuki being the man in his matches vs. these opponents, and these matches both being notably better than Shamrock vs. Sano, it's more clear that he's the leading light in this promotion. Suzuki is really grasping the urgency as well, if not better than anyone. Even though his arsenal floats somewhere between pro wrestler & what we'd come to know as an MMA fighter, he does it with so much speed & desperation that the same technique comes off almost completely different than in a traditional pro wrestling style match. This feels like a struggle, like there's real danger if you are unable to react to them before they can react to you. The fact he was not only able to accomplish this, but keep it up for the majority of a half hour match where he also managed to take things down seemingly not to rest, but rather to set up further escalation with another wild dramatic burst that didn't feel false was pretty remarkable. It's difficult to keep the illusion of a shoot alive for 5 minutes, but the incredible tension that these two are able to sustain throughout such a long contest is really what sets it apart. I don't want to make it sound like this was all Suzuki, Sano was growing in this style by leaps and bounds. You can see that his confidence is so much higher here than it was against Shamrock on the previous show, and he's just flowing a lot better, really on point with his reactions as well so it doesn't feel like pro wrestling cooperation. Sano again allowed the opponent to lead, but Suzuki is a lot better leader than Shamrock, and Sano is a better opponent for Suzuki in the reaction style because speedy offense & counter laden chain wrestling are the backbones of the junior heavyweight wrestling he's so good at. Although Sano is the newbie in U-style, he's the veteran in this match, and he's able to show that by staying composed and trusting that, unpredictable as Suzuki may be, he still has the counter/answer to anything Suzuki can throw at him. The match was very spot oriented, but they did a good job of just avoiding or immediately defending the submissions so they weren't straining the credibility for so called drama with the minute armbar before the opponent finally finished sliding to the ropes shenanigans. I won't say that they didn't strain credibility, I mean, Suzuki tried his dropkick, but they did so only by performing fast, explosive moves. Still, I liked the first half better when things were more under control than the second half when, ironically, what began to make the match look like it would be a draw was that they started hitting high spots that would have been finishes if they were used at all in PWFG, but they weren't getting the job done. That being said, this managed to be both exciting enough to be a great pro wrestling match of the era and credible enough to be a great shoot style match of the era. The weakness of the match was the transitions from the striking sequences to the mat sequences, not so much because they lacked great ways to get it to the mat, though that's also true, but mainly because they really only knew a bit of Greco-Roman based wrestling, so the action kind of artificially stalled out in a sort of minimal exertion mid-ring clinch while they plotted their explosion to get into the next great mat sequence. This aspect did improve as the match progressed with the introduction of knees, but this is also where they started incorporating the pro wrestling maneuvers. Though Sano is the spot merchant in pro wrestling, it was actually Suzuki that was initiating the more suspect spots here, with Sano shrugging them off. I though the no cooperation belly-to-belly suplex was good precisely because it wasn't cleanly performed, but I could have lived without the later versions, the piledriver, and a few other flourishes. Suzuki did a great job of blending pro wrestling affectations with shoot style desperation though. For instance, chopping Sano's wrist to try to break his clasp that was defending the armbar or slapping his own face to keep himself from from going to sleep in a choke were nice dramatic nods even though they obviously aren't what you'd learn from Firas Zahabi. The crowd was pretty rapid throughout for this big interpromotional match, probably the best reactions PWFG has gotten so far, as they were really eating this up. It felt like Sano really pulled ahead midway through the contest when Suzuki initiated a barrage of strikes, even using body punches, but Sano ultimately won what turned into a palm blow exchange, dropping & bloodying Minoru. However, Suzuki had more stamina than Sano, and as the match progressed he began to be too quick for Sano, and was now getting strikes through that had previously been avoided. Sano may well have just been blown up, but it added to the story without reducing the quality in any way. The contest finally climaxed with both working leg locks as the 30-minute time limit expired. You'd think PWFG would want Sano back as soon as possible, and the draw should have led to a rematch at some point, but sadly Suzuki was the only native Sano ever fought in PWFG, with his remaining 3 bouts being against Vale and Flynn. ****1/2

MB: This was a treat, and one of the best matches, shoot-style or otherwise, that we have seen up to this point. A fast paced 30 minute war that featured all sorts of grappling that was ahead of its time for most audiences. Guillotine chokes, ankle picks, half guard work, armbars, and heel hooks were spliced together with more standard pro wrestling fare, and terse striking exchanges. The striking in this match was also very logical, in that they would focus on the grappling first, and when that seemed to stall out, then one would break up the monotony with strikes in an effort to force a change, or create an opening. There was some pro wrestling tomfoolery, (at one point Suzuki gave Sano a piledriver as he was warding off a takedown with a sprawl/underhook technique) but it didn't detract from the match, in fact because the flashier spots were used sparingly and towards the end of the match, it did have the effect of spicing things up a bit towards the end. This match showed us that despite their flaws, the PWFG was the best of the Shoot-Style promotions at this point in time, and had the potential for something truly extraordinary.

7/30/91: Kazuo Yamazaki vs. Billy Scott 12:39. Yamazaki hasn't exactly had a great opportunity to shine yet. After frustratingly getting strapped with the Southern man, who clearly couldn't keep his head, he now found himself involved in the trial of Billy Jack. Luckily though, Scott, who wound up being my favorite American fighter in the promotion (other than monster for hire Vader, who almost doesn't count given his matches were almost purely powerbomb driven pro wrestling beatdowns), shows a good deal of ability even in his debut. What set this match apart was their ability to tantalize the audience through a display of defense. This wasn't a match where they'd lock the submission, and then 45 seconds later the opponent magically grabbed the ropes, it's a match where they always seemed close to something on the mat, but rarely got it. Early on, they kept testing each other, kind of for the fun of it, with the fighter who defended the move trying his hand at it, and failing as well. They really had the answers for each other in standup, with Yamazaki being ready for Scott's single leg takedown, which seemed to be Billy's biggest weapon from his amateur wrestling days, and Scott avoiding taking too many of Yamazaki's kicks, answering aggressively to at least take away Yamazaki's space so he had to grapple with Scott instead. Yamazaki was a massive favorite here as he's the #2 fighter in the promotion going against some new guy from Tennessee, a place where wrestlers seemingly only know how to throw punches, yet still have no actual footwork or technique. Yamazaki is somewhat subdued early, just testing Scott out & seeing what he has to offer, while Scott is much more excitable, which is his personality anyway, but the difference especially makes sense here given he's the new guy trying to make a strong impression against a top dog who sees this more as a tune-up/sparring kind of walkover. Yamazaki tends to be a step ahead for the first 10 minutes. Though he's not running away with the contest by any means, you can see his brilliance in the story of the match where he sets up Scott turning the tide & actually becoming a threat to win when Scott finally catches Yamazaki's kick & counters with a back suplex into a 1/2 crab for the matches big near submission. The fans were instantly ignited, chanting "Yama-zaki" because in the context of the bout they've been viewing, someone actually being trapped in a submission, especially mid ring, is a real threat. Yamazaki does a great job of putting the submission over by not going over the top, taking a down after a rope escape trying to recover, & then still just stalling by fixing his kneepads to try to steal Scott's momentum. Yamazaki then coming back with high kicks somewhat defeated the purpose though. This was really the time for Scott to have a minute or two with Yamazaki in danger to show what he could do before Yamazaki turned the tide back and perhaps won, and while that's mostly what happened with Scott coming right back with a belly to belly suplex & working for an STF, the transition to the finishing segment was a bit abrupt & the segment itself felt rushed, as was the case with Miyato/Nakano earlier in the night. Both matches felt like the workers may have been finding their way to a pre scripted finishing sequence, but these two did a better job of having a match before that & finding a way to stay true to it rather than just biding time until the usual UWF-I flashiness. As a whole, Yamazaki/Scott worked quite well because they kept active enough that the fans cared about them coming close but not quite getting there, and the drama kept increasing. In the end, not a lot happened by the usual UWF-I pro wrestling standards, but much of what made it good is they were successful in teasing the audience that things almost happened. This was certainly more credible than the usual no resistance exchanges, and to me, much more exciting and dramatic because of that. ***1/4

7/30/91: Kazuo Yamazaki vs. Billy Scott 12:39. Yamazaki hasn't exactly had a great opportunity to shine yet. After frustratingly getting strapped with the Southern man, who clearly couldn't keep his head, he now found himself involved in the trial of Billy Jack. Luckily though, Scott, who wound up being my favorite American fighter in the promotion (other than monster for hire Vader, who almost doesn't count given his matches were almost purely powerbomb driven pro wrestling beatdowns), shows a good deal of ability even in his debut. What set this match apart was their ability to tantalize the audience through a display of defense. This wasn't a match where they'd lock the submission, and then 45 seconds later the opponent magically grabbed the ropes, it's a match where they always seemed close to something on the mat, but rarely got it. Early on, they kept testing each other, kind of for the fun of it, with the fighter who defended the move trying his hand at it, and failing as well. They really had the answers for each other in standup, with Yamazaki being ready for Scott's single leg takedown, which seemed to be Billy's biggest weapon from his amateur wrestling days, and Scott avoiding taking too many of Yamazaki's kicks, answering aggressively to at least take away Yamazaki's space so he had to grapple with Scott instead. Yamazaki was a massive favorite here as he's the #2 fighter in the promotion going against some new guy from Tennessee, a place where wrestlers seemingly only know how to throw punches, yet still have no actual footwork or technique. Yamazaki is somewhat subdued early, just testing Scott out & seeing what he has to offer, while Scott is much more excitable, which is his personality anyway, but the difference especially makes sense here given he's the new guy trying to make a strong impression against a top dog who sees this more as a tune-up/sparring kind of walkover. Yamazaki tends to be a step ahead for the first 10 minutes. Though he's not running away with the contest by any means, you can see his brilliance in the story of the match where he sets up Scott turning the tide & actually becoming a threat to win when Scott finally catches Yamazaki's kick & counters with a back suplex into a 1/2 crab for the matches big near submission. The fans were instantly ignited, chanting "Yama-zaki" because in the context of the bout they've been viewing, someone actually being trapped in a submission, especially mid ring, is a real threat. Yamazaki does a great job of putting the submission over by not going over the top, taking a down after a rope escape trying to recover, & then still just stalling by fixing his kneepads to try to steal Scott's momentum. Yamazaki then coming back with high kicks somewhat defeated the purpose though. This was really the time for Scott to have a minute or two with Yamazaki in danger to show what he could do before Yamazaki turned the tide back and perhaps won, and while that's mostly what happened with Scott coming right back with a belly to belly suplex & working for an STF, the transition to the finishing segment was a bit abrupt & the segment itself felt rushed, as was the case with Miyato/Nakano earlier in the night. Both matches felt like the workers may have been finding their way to a pre scripted finishing sequence, but these two did a better job of having a match before that & finding a way to stay true to it rather than just biding time until the usual UWF-I flashiness. As a whole, Yamazaki/Scott worked quite well because they kept active enough that the fans cared about them coming close but not quite getting there, and the drama kept increasing. In the end, not a lot happened by the usual UWF-I pro wrestling standards, but much of what made it good is they were successful in teasing the audience that things almost happened. This was certainly more credible than the usual no resistance exchanges, and to me, much more exciting and dramatic because of that. ***1/4

MB: Scott must face the ultimate trial by fire, and have his very first professional wrestling match, against the seasoned Yamazaki. We can see that Scott is the best Gaijin that the promotion has seen so far, as he actually moves like someone with a solid wrestling pedigree, but unlike Tom Burton, he has the speed and fluidity to go with it. The first couple of minutes have them feeling each other out, with Scott faking some shooting attempts, and Yamazaki feeling out his opponents' distance with some fast kicks. Scott succeeds with a takedown, but his training in submissions must have been limited to the school of "crank on something, and hope for the best," which doesn't faze Yamazaki in the slightest. The match followed the pattern of Scott being the takedown artist, but not being able to pin Yamazaki down for long, or lock in an intelligible submission. Yamazaki would keep finding crafty ways to transition out of his predicament and turn in it into a leg/ankle attack. Eventually, Yamazaki got the win when his Scott came rushing at him with his head down, and he was able to slap on some kind of version of a standing arm-triangle choke. What was great about this match was that they went into it with the mindset of having to feint, set up attacks, and actually work for a takedown or submission attempt, as opposed to just handing everything to each other. Unlike much of the overtly choreographed wrestling of the past, it seems that this style can allow its practitioners the ability to shoot for good portions of the match (at least in terms of positioning) and sprinkle in cooperation in others. In any event, Yamazaki was a master of ring psychology, and to his credit, Billy Scott showed a lot of poise for a rookie, and had good patience and movement. His submission acumen needs work, but that can surely improve in time. It's very likely that the UWFI has secured a great talent in Scott, and I hope to see him improve in the days to come.